The lack of private sector job creation in B.C. should be setting off alarm bells

In June total employment in B.C. fell by 10,000. The setback follows a similar sized decline in May. Despite the two month-to-month losses, the average employment level in Q2 was 1.9 per cent higher than in Q2 2023, a modest but decent gain. From this snapshot one might conclude B.C.’s job market is soft but still in reasonably good shape. But the reality could hardly be more different. Private sector job growth is the weakest it has ever been and the only reason overall employment in B.C. has grown in recent years is because of the unprecedented expansion in public sector hiring. When contrasted with other provinces the situation in B.C. is even more concerning. In other provinces the public sector has played an out-sized role in job creation, but nothing like in B.C.

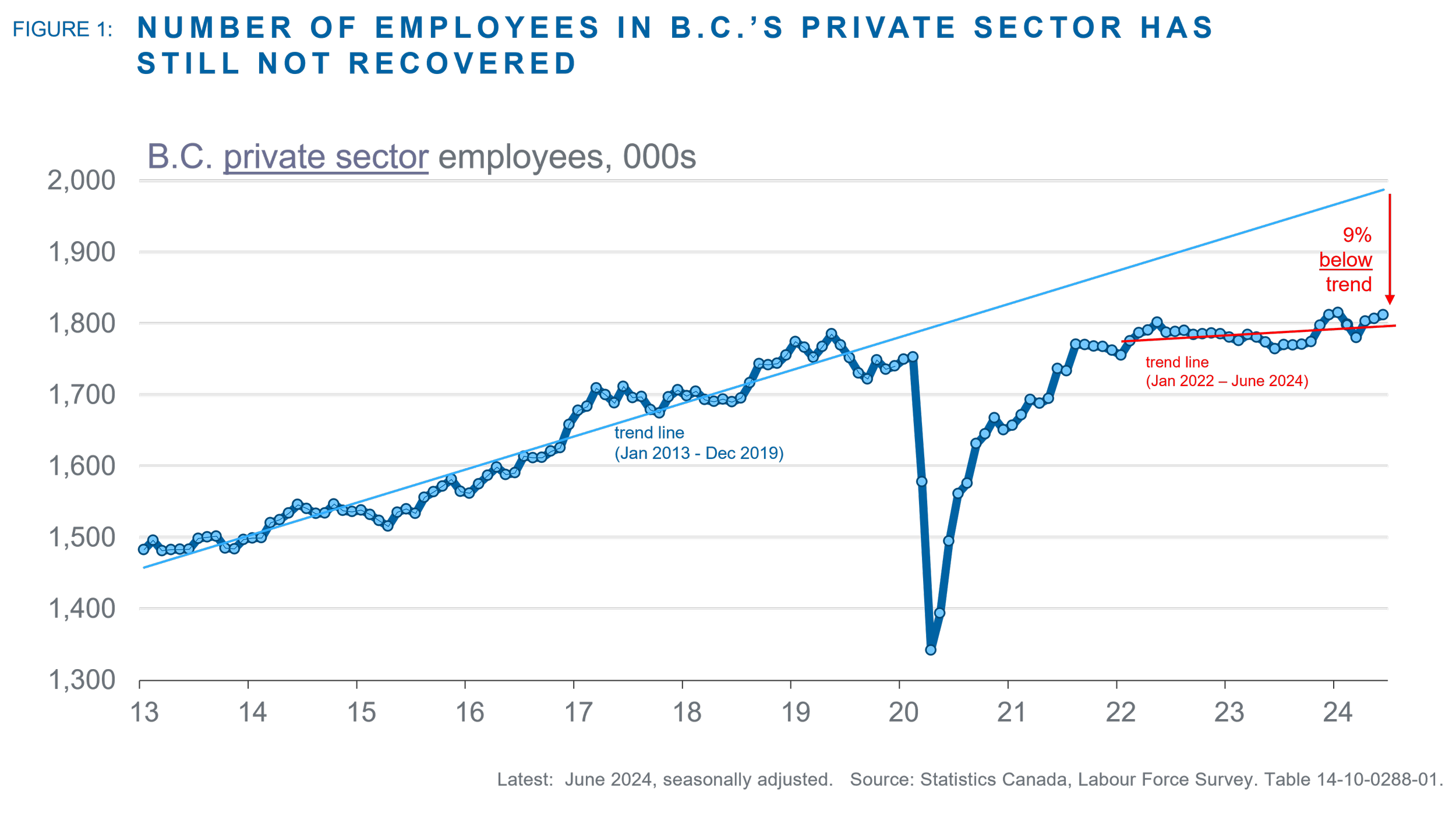

Figure 1 below shows the number of employees in B.C.’s private sector since 2013. A trend line for the period spanning January 2013 to December 2019 is included with the trend projected to 2024. This extrapolation is a simple “forecast” of how many employees could be expected in B.C.’s private sector if on average in the ensuing years investment, growth and hiring activity had remained the same as in the seven-year period prior to the pandemic. Figure 1 also shows a trend line of the most recent two-and-a-half-year period (red line). From the trend lines, we estimate the number of employees in the private sector is 180,000, or 9 per cent, below the “business as usual” extrapolation.

Over the January 2022 to June 2024 period there is little indication that private sector hiring is picking up. Instead, the unusually anemic growth in private sector employees means the gap between the recent trend and the pre-pandemic trend in private sector hiring continues to widen.

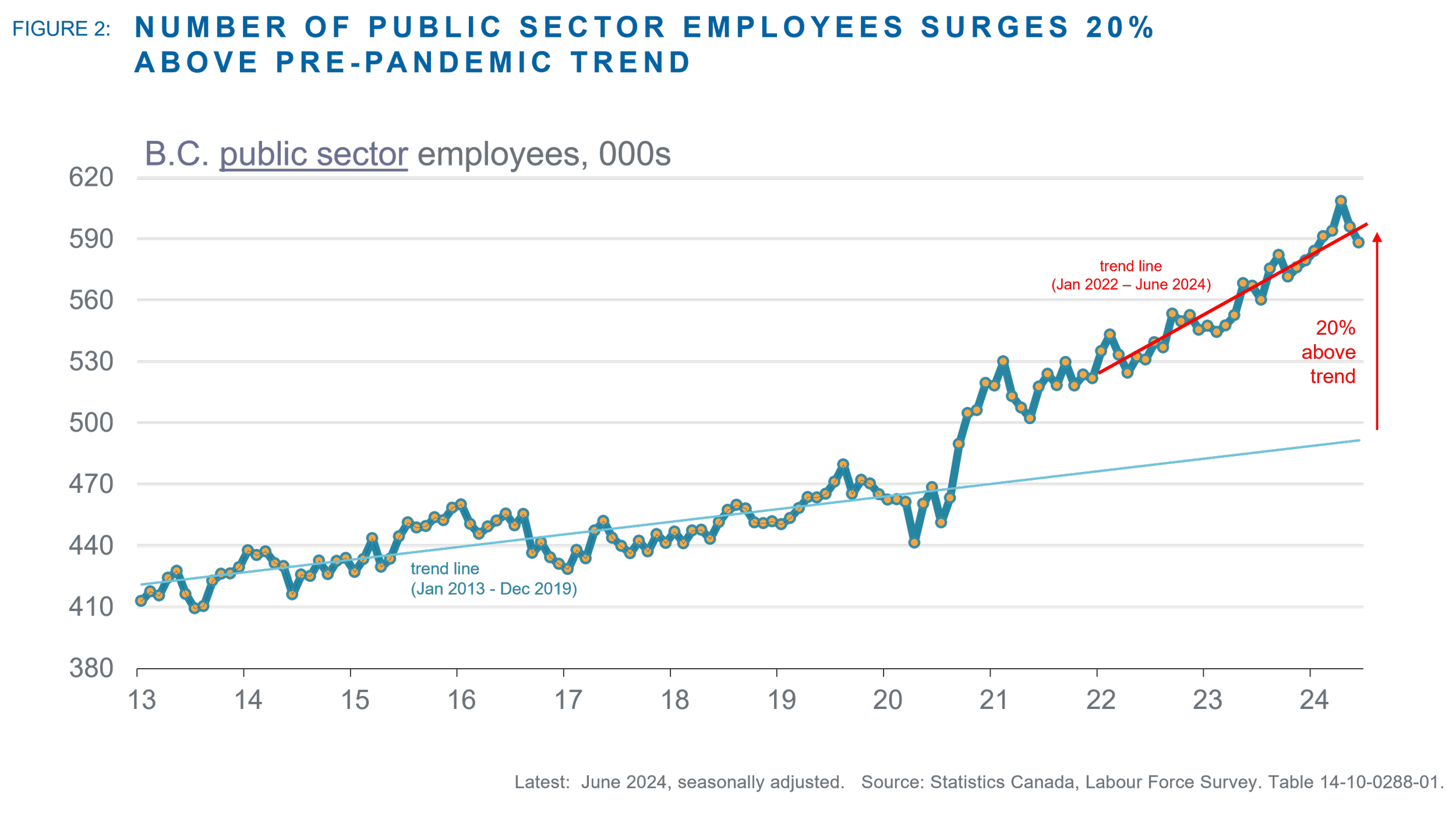

Figure 2 shows the number of public sector employees in B.C. over the same period and includes the same pre-pandemic and more recent trend lines. The number of employees in B.C.’s public sector has surged since 2020 and is currently almost 100,000 (20 per cent) higher than the “business as usual” pre-pandemic trend projection.

The other broad class of worker is self-employment. In B.C., self-employment is about 40,000 (7.7%) below trend. Here we are concerned about investment and hiring conditions so our focus is on payroll employees. A similar figure to Figures 1 and 2 is shown for self-employment in the Appendix.

Growth in private sector employment in B.C. has been weak for several years, culminating in a large shortfall in the number of people working in the private sector below expected levels. Indeed, the number of private sector employees in B.C. is not much higher than in 2019. In B.C. the only reason overall employment levels have increased is because of the record expansion in public sector employment.

The picture is very different elsewhere in Canada

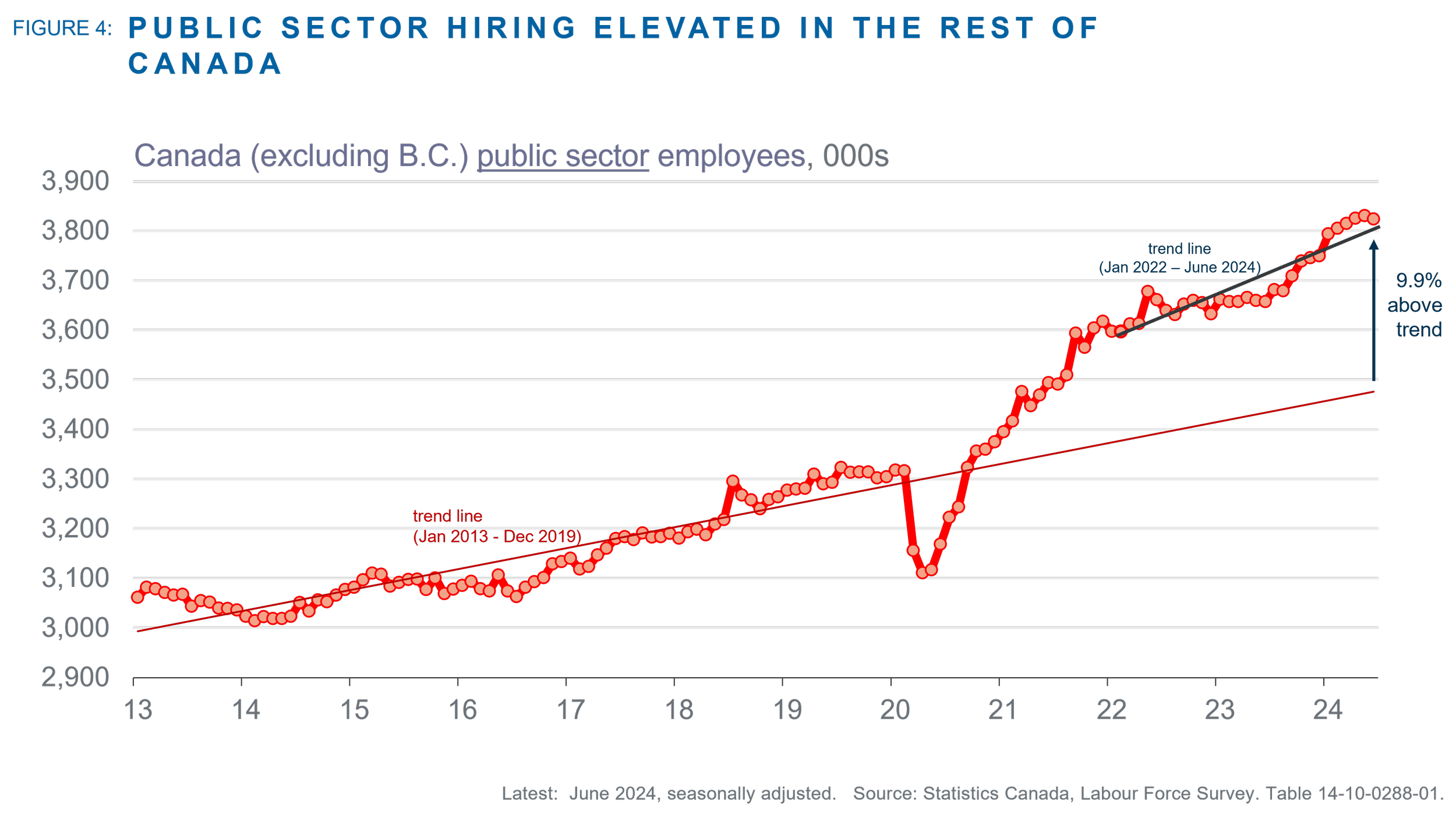

In the other provinces the situation is very different. Overall employment has been boosted by strong public sector hiring but the private sector has also generated jobs. Figure 4 shows the number of private sector employees in the rest of Canada (Canada less B.C.) and the same trend lines as in the figures showing B.C. employment. In contrast to B.C., the number of employees in the private sector in the rest of Canada has “more than recovered” from the pandemic and is currently 400,000 (3.6%) above the pre-pandemic trend line.

Like B.C., the rest of Canada has also seen out-sized growth in public sector employment. Figure 4 shows the number of public sector employees in the rest of Canada is currently 340,000 above the 2013-2019 trend line projection. For the rest of Canada this means public sector employment is almost 10 per cent above trend whereas in B.C. public sector employment is 20 per cent above trend.

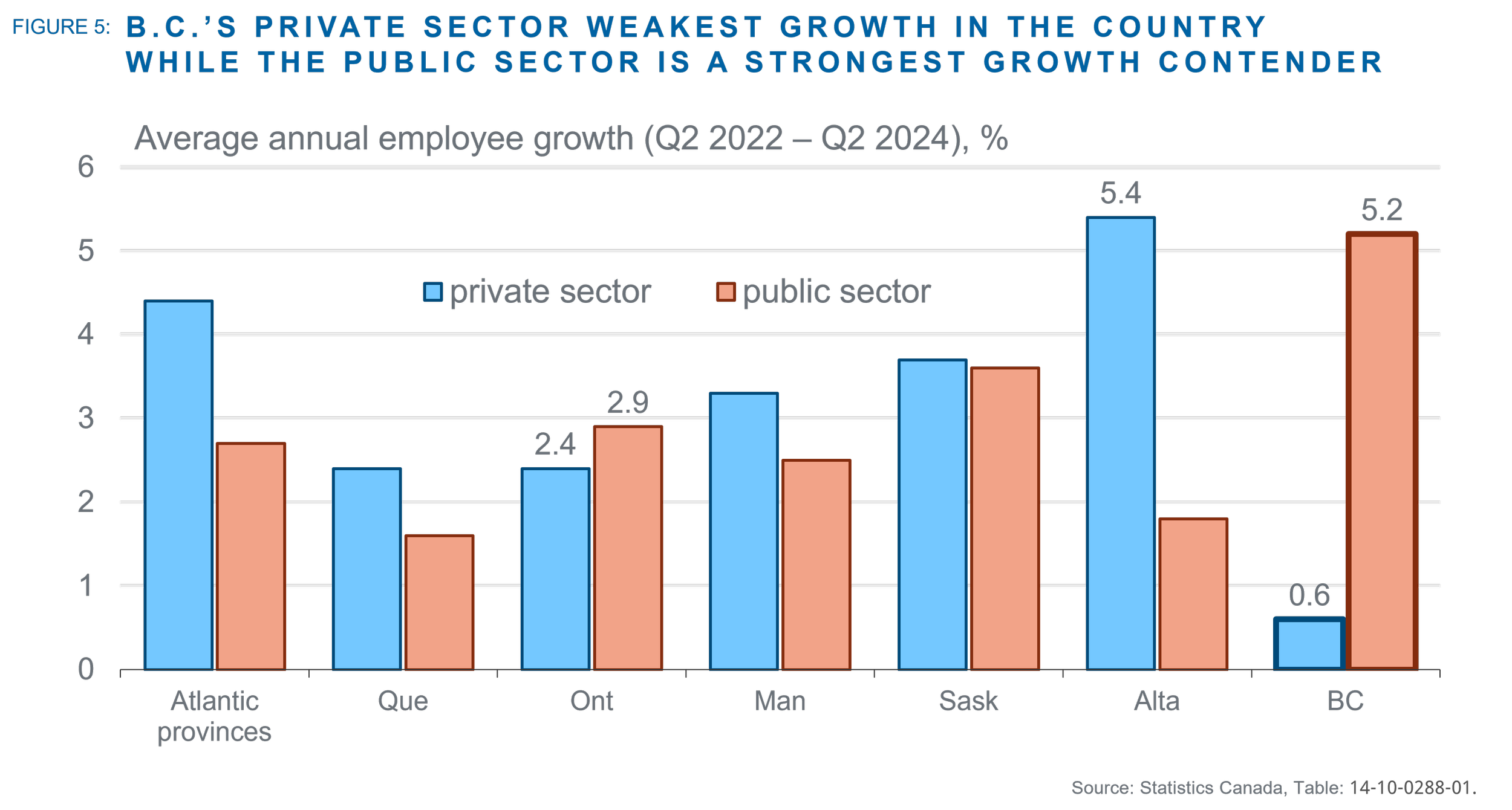

Figure 5 summarizes growth in public and private sector employment across provinces and further underscores the degree to which labour market conditions in B.C. differ. The number of employees in B.C.’s private sector has grown at an average annual rate of just 0.6 per cent over the past two years, the slowest of any class of worker in any province. In sharp contrast the number of employees in B.C.’s public sector has grown by an average annual rate of 5.2 per cent, vying with the Alberta’s private sector for top spot overall.

This means that B.C. public sector employment has grown nine times faster than private sector employment over the past couple of years. In the other provinces, apart from Ontario, private sector employment growth has been stronger than the public sector. And at least in Ontario growth in the private and public sectors is somewhat aligned.

Weak private sector hiring evident in B.C. for half a decade

Remarkably, the picture is essentially the same over the past five years: very weak private sector job creation in B.C. while public sector employment surged higher. Consistent with the pattern over the past two years, B.C. is also bottom of the rankings in the number of new private sector employees and top in public sector employee growth since 2019.

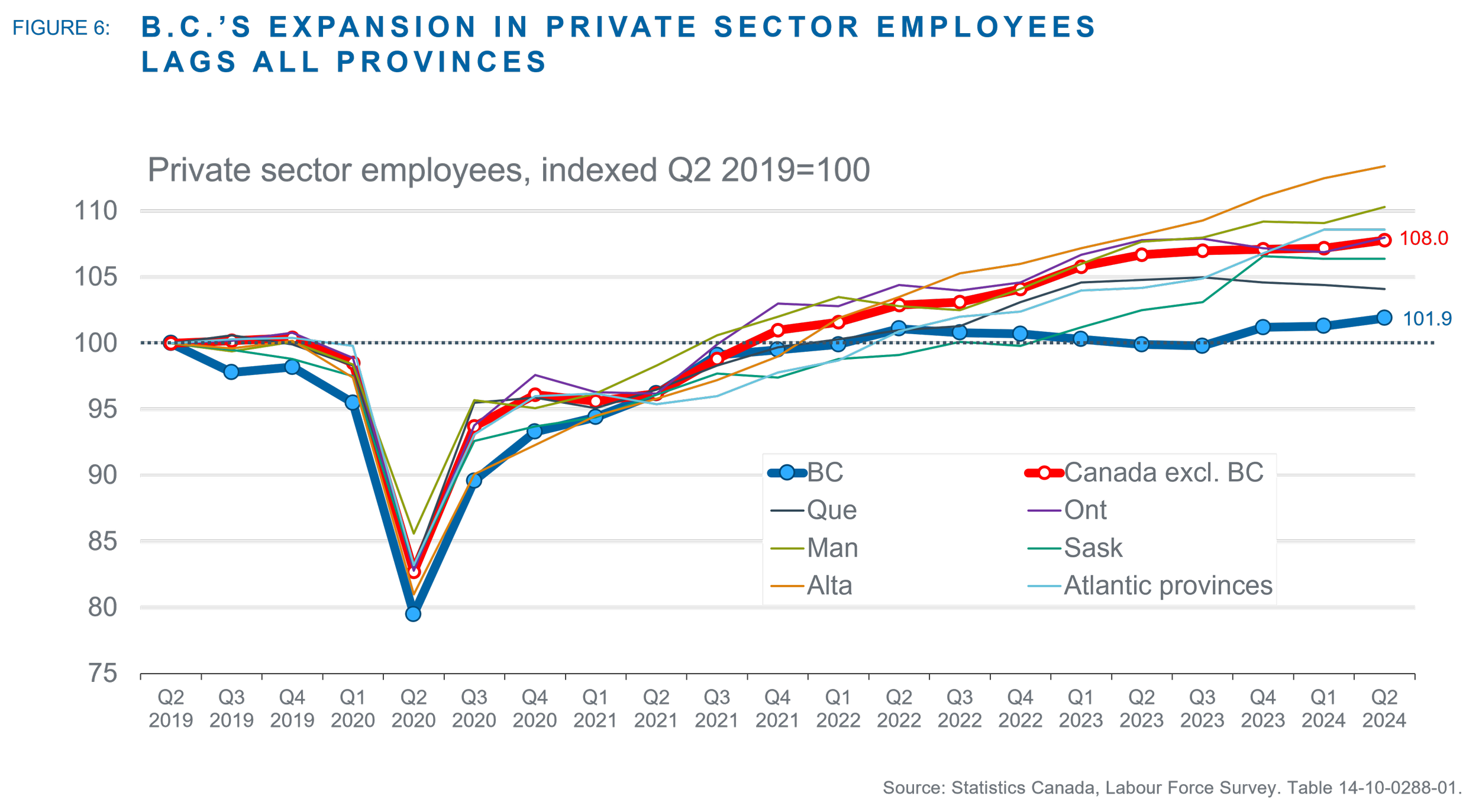

Heading into the pandemic, private sector employment was already slipping in B.C. Employment tumbled with the COVID closures and private sector employee counts fell further in B.C. than any other province by Q2 2020 (relative to Q2 2019). Private sector employment was slower to regain pre-pandemic levels than most provinces. And B.C. has seen the weakest private sector employment growth since Q2 2019 of any province (Figure 6).

Precisely the reverse is true for the public sector. B.C. saw the smallest decline in public sector employment during the pandemic, recorded the largest jump coming out of the pandemic and has registered the biggest surge in public sector payrolls of any province since Q2 2019 (Figure 7).

The situation in B.C. is not sustainable

The ratio of private sector hiring to public sector hiring further underscores just how different and unsustainable the situation in B.C. is. Over the past five years (between Q2 2019 and Q2 of 2024) B.C. has seen just 0.3 employees hired in the private sector for every additional employee hired in the public sector. Looking at just the past two years when the COVID labour market distortions had mostly passed, the ratio declined to 0.2 new employees.

The comparable ratio has increased in every other province, indicating private sector hiring has strengthened in the past two years relative to the longer five-year period. The ratio in Ontario and Quebec is 2.1 and 2.0 over the past two years. This indicates hiring remains too heavily skewed towards the public sector (considering the private sector employs three times as many people), but nothing close to the situation in B.C. Over the past two years Saskatchewan and Manitoba have seen 4.6 and 4.9 additional employees hired in the private sector for every additional employee hired in the public sector. In Alberta the private sector has hired 13.2 new employees for every employee hired in the public sector over the past two years.

Policy makers in B.C. should be ringing alarm bells. The reality is public sector employment has surged higher while private sector employment has inched ahead over the past five years. It is concerning there is little indication the pattern is changing. The degree to which the malaise in private sector hiring is unique to B.C. is especially worrisome. It suggests businesses are not investing and expanding in B.C. and that escalating payroll and operating costs are weighing on investment and job creation disproportionately in the province. Government revenues used to pay public sector wages and salaries are raised through taxes and fees levied on the private sector. The private sector creating a fraction of an additional employee for every additional employee added to the public sector is a ratio that cannot be sustained. Eventually swelling public sector payrolls lead to spending and fiscal pressures. It should not escape the notice of British Columbians and policy makers that this fiscal year the NDP government is planning on running the largest deficit in B.C.’s history, while other provinces are planning on balancing their budgets or running small deficits. B.C. is also planning on running similarly large deficits in the next two fiscal years. Absent stronger private sector job creation the province’s fiscal circumstances will continue to deteriorate.

Appendix

The number of self-employed persons in B.C. is 7.7 per cent below trend, or about 40,000 jobs. Growth in self employment has been stronger recently and is trending back towards the longer-term pre-pandemic trend.