Saving lives and livelihoods during the COVID-19 pandemic

Note - The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the board or members of BCBC.

The COVID-19 pandemic is the most serious public health and economic crisis in the past century. The outbreak is believed to have started when a species-jumping novel coronavirus emerged at a wild animal market in Wuhan, China, in or about November 2019 (see here and here). For a few weeks, a small but crucial window to contain the outbreak was missed as cases increased by 1-5 per day. As at December 15, the number of cases stood at 27. The Chinese government reported the outbreak to the World Health Organization (WHO) on 31 December 2019, by which time the number of cases had jumped to 266.

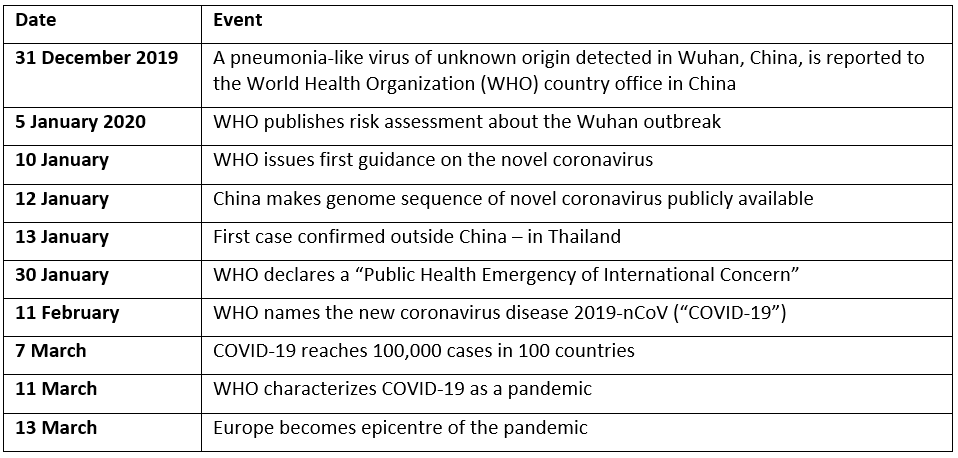

Table 1: Timeline of the COVID-19 outbreak

Source: World Health Organization (WHO).

The epidemiological curve

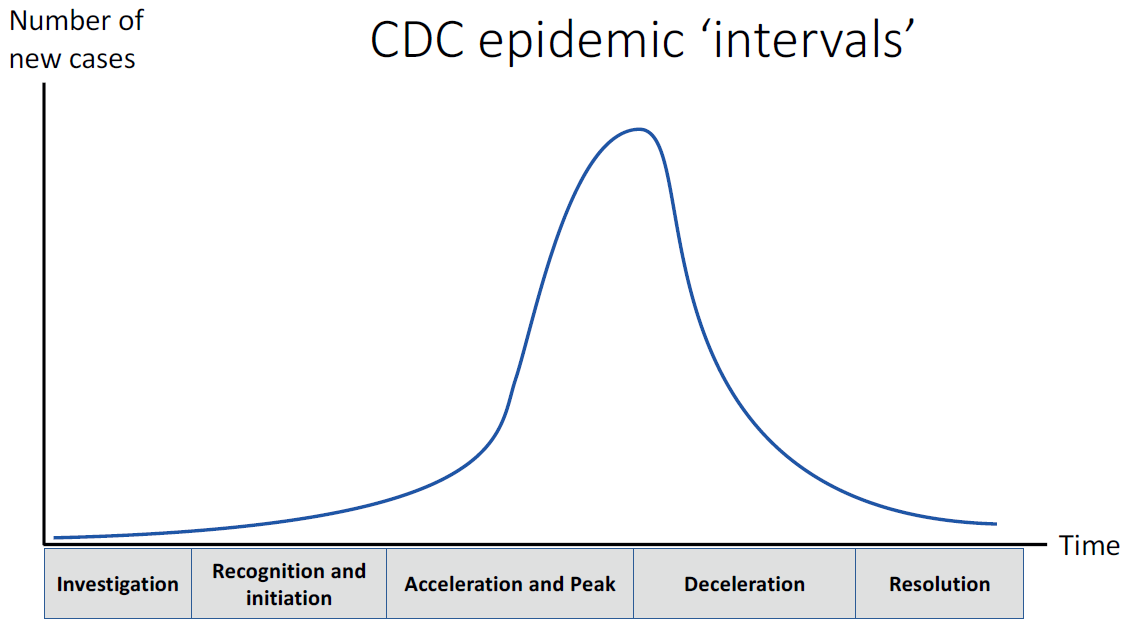

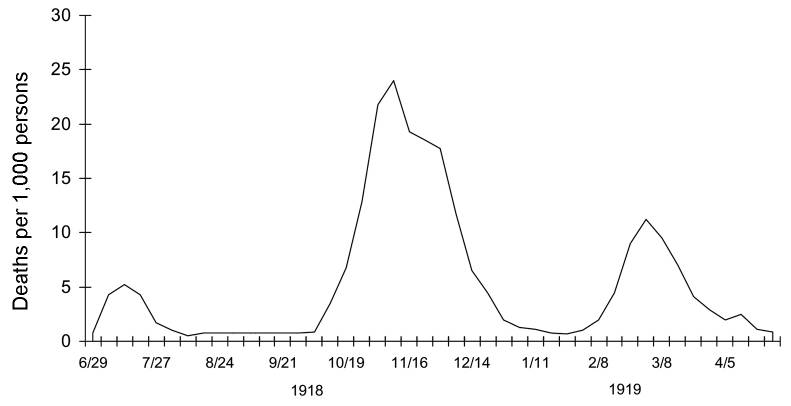

As at March, most advanced countries appear to be in the acceleration phase of the epidemiological curve (Figure 1). The number of cases globally is now over 440,000 including almost 3,000 cases in Canada and more than 600 in B.C. The curve may surge several times over coming months. The so-called “Spanish influenza” pandemic lasted from January 1918 until December 1920. It had three waves, with the second surge in late 1918 being the largest (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The epidemiological curve (single wave)

Source: Baldwin and Weber di Mauro (2020).

Figure 2: Spanish influenza mortality in the United Kingdom

Source: Taubenberger and Morens (2006).

In an epidemic, the number of cases grows exponentially until the virus starts to run out of susceptible persons to infect through physical separation, immunity or a vaccine. To slow down or flatten the epidemiological curve, the first line of defence is to test, trace contacts and quarantine or isolate suspected cases. As a second line of defence, to take pressure off the acute care health system, governments around the world are taking steps around:

Physical distancing by reducing the number of person-to-person contacts across the population that provide opportunities for virus transmission. These strategies revolve around social and economic inactivity, including bans on mass or small group gatherings, moving to virtual working, and partial or outright business closures.

Reducing the probability of infection when in contact with someone carrying the virus.Strategies include frequent hand washing and cleaning of high touch surfaces, and for health care workers, use of masks, gowns and other protective equipment.

Shuttering the economy – how far should governments go?

Governments, including in Canada, are deliberately deactivating much of the economy to avert a public health crisis. The more inactive people become, the slower the virus is likely to spread (Figure 3). It is a cruel tradeoff: saving lives but destroying livelihoods.

Economists tend to think about societal problems as constrained rather than unconstrained optimization problems. In that view, governments should be adopting measures that achieve the greatest reduction in direct interpersonal contact across the population for the least economic cost. For example, it is highly beneficial and relatively costless to temporarily ban social gatherings of more than two people not of the same household, as Germany has done.

Governments should be mindful in setting policies about which businesses can keep operating, albeit in a risk-mitigated and limited way, and which cannot operate at all. Essential businesses like utilities, grocery, agriculture, rail and trucking, ports, petrol stations, chemical manufacturers and the logistics industry must stay open. Some grocery stores in B.C. are installing tape and plastic screens to separate workers from customers.

Arguably, there are other non-essential businesses that have low levels of physical interaction and would result in negligible public health gains from being shut down. This includes parts of the industrial economy where physical interaction between workers is low and, with the sort of ingenuity shown by the grocery store example above, could be reduced further. In the months ahead, the economy will need every dollar of income and tax revenue it can get to feed, shelter and pay much of the population to stay home and inactive. This underscores the importance of maintaining business activity in at least some sectors.

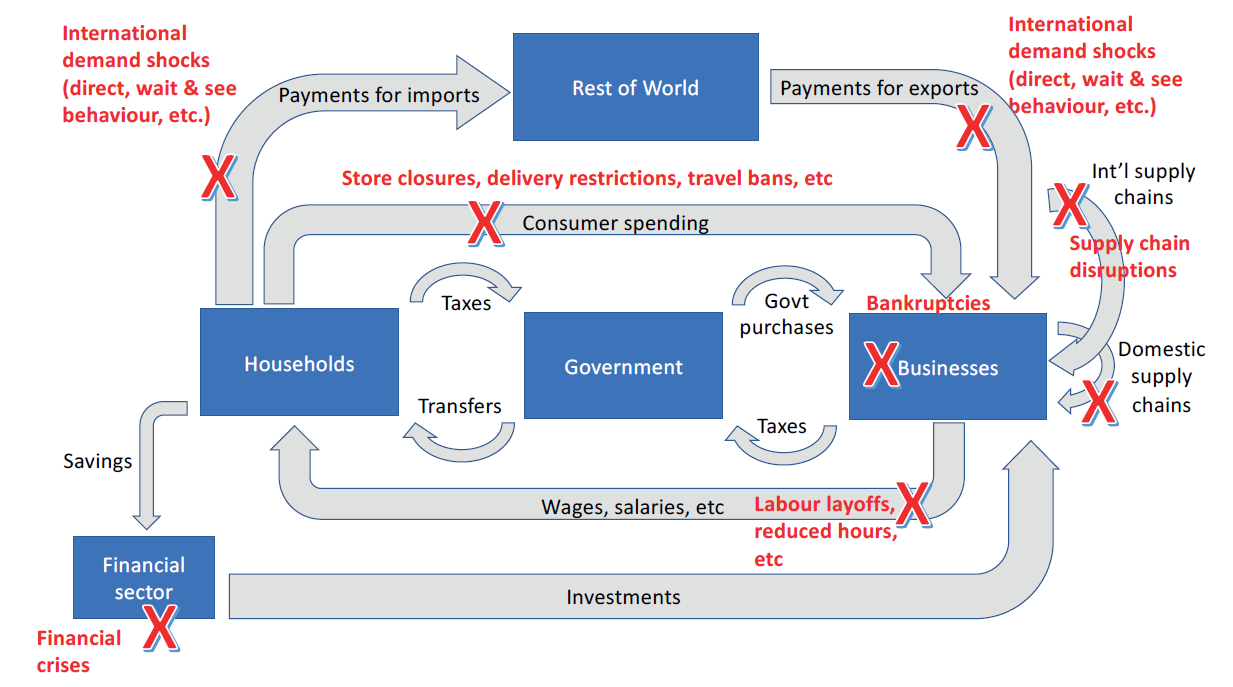

Figure 3: Lives and livelihoods – COVID-19’s cruel tradeoff

Source: Baldwin and Weber di Mauro (2020).

The deep freeze

Canada did not fix its roof before the rain. Going into 2020, the country had low levels of capital investment, declining productivity relative to other advanced countries, and the 7thhighest level of national indebtedness globally at 302% of GDP. In order to manage the downturn and prevent a serious economic or financial crisis, the federal government will need to swiftly and massively expand supports for all sectors of the economy.

A circular flow diagram provides a stylized way to think about the flow of income, capital and goods and services between various sectors of the economy: households, businesses, governments, the financial sector and the rest of the world. As Figure 4 shows, the deliberate, sudden scaling back of economic activity will induce incredible disruptions to these flows. We will see unemployment, evictions, business closures, defaults, bankruptcies, foreclosures, supply chain disruptions and pressure on financial institutions. It will be important for governments to design policies that address all of these disruptions. Federal and provincial government support measures need to be massive, broadly available, immediate, flexible and sustained for many months.

Figure 4: Disruptions to the circular flow

Source: Baldwin and Weber di Mauro (2020).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic presents extraordinary public health and economic challenges that are diametrically opposed in outcome. Potentially, the fewer people that lose their lives, the more that will lose their livelihoods, and vice versa. It is the cruelest of policy dilemmas.

Priority one is to support and increase the capacity of the acute health care system and COVID-19 testing and contact tracing. Health care workers and the supply chains that support them to save lives should be governments’ paramount concern. Priority two is that Canada needs to drastically reduce physical interactions across the population to slow the pandemic and thus reduce pressure on the health care system. However, priority three is that Canada also needs every dollar and job it can safely sustain to feed, shelter and pay large numbers of Canadians to stay home and inactive.

Governments should therefore be mindful in thinking about (a) what business must not operate, (b) what businesses must not close, and (c) what middle ground exists where a business might be able to remain operational in a limited and risk-mitigated way. The goal should be to achieve as much physical distancing and infection mitigation as possible at the least economic cost. As much of the consumer-based economy is shuttered, governments should be looking to the industrial and digital economies to operate safely and support the rest of the country.

Priority four is that government must provide palliative relief for the pain its medicine will cause. To stave off potential economic and financial crises, swift and judicious government interventions are needed that can keep income, goods and services, and capital flowing. Such interventions need to be immediate, intelligent, massive and sustained. We are all in this together.