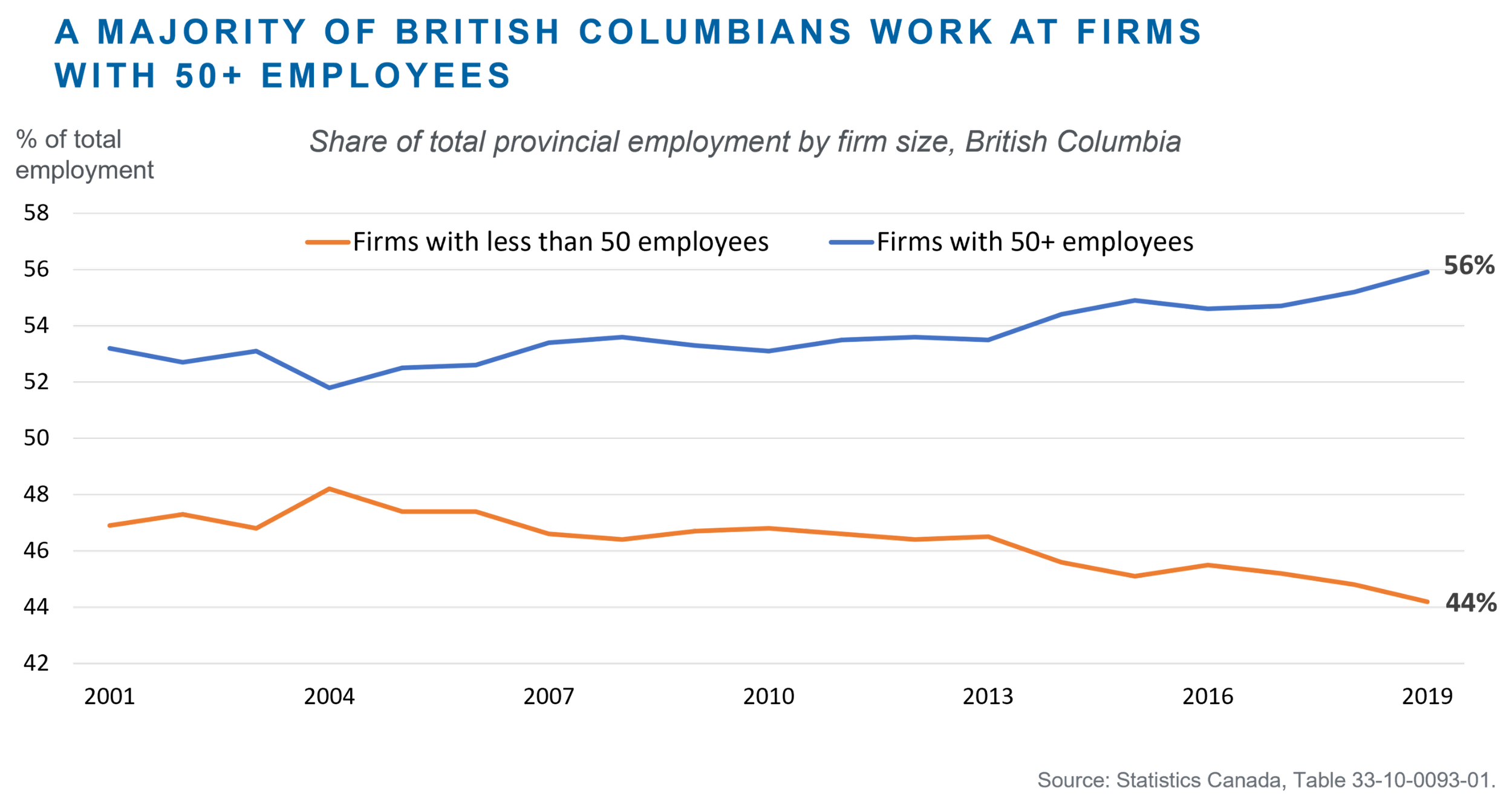

B.C. businesses are growing up: Firms with 50+ employees make up 56% of provincial employment

An increasing majority of British Columbians work at firms with at least 50 employees. That’s the takeaway from recent Statistics Canada data on the share of provincial employment by firm size. In 2019, firms with at least 50 employees accounted for 56% of B.C.’s total workforce, up from 53% in 2001 (Figure 1). The share of private sector workers in firms with 50 or more employees was even greater. Most of the increase from 2001 to 2019 was among large firms with at least 500 employees (see below and Figure 2).[1]

Meanwhile, the share of B.C. jobs at firms with less than 50 employees declined from 47% in 2001 to 44% in 2019.

Figure 1

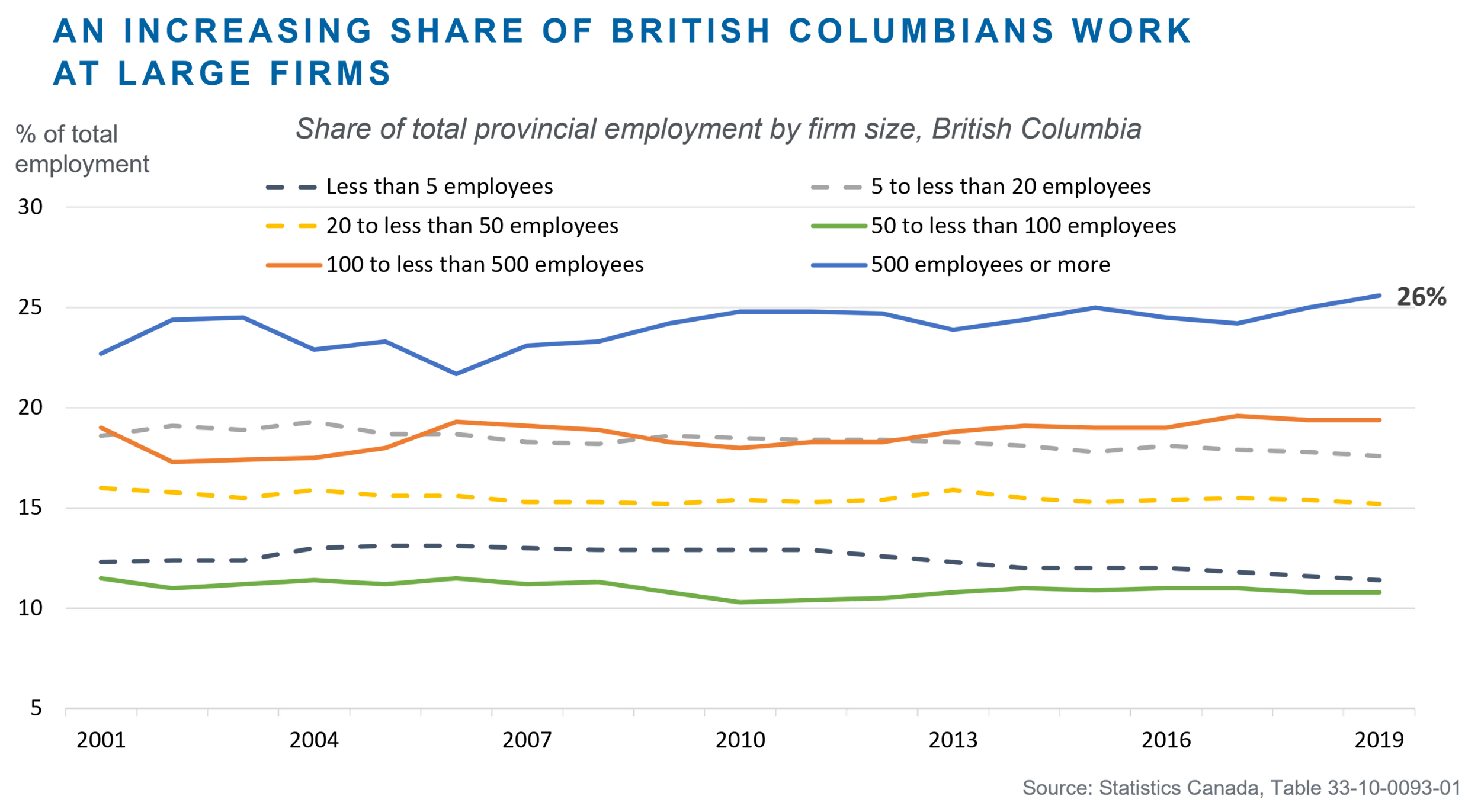

Large firms make up an increasing share of provincial employment

Figure 2 provides more detail. Large firms, those with 500+ employees, represented around 26% of total provincial employment in 2019, up from 23% in 2001. Mid-sized firms, those with 100-499 employees, contributed a steady 19% of total employment.

The share of provincial employment among small firms declined over 2001-2019. The share of total B.C. employment declined by about 1 percentage point between 2001-2019, respectively, among firms with less than 5 employees, 5-19 employees, 20-49 employees and 50-99 employees. The diminishing importance of small businesses as a source of jobs in B.C. runs counter to the narrative often espoused by politicians and other government officials.

Figure 2

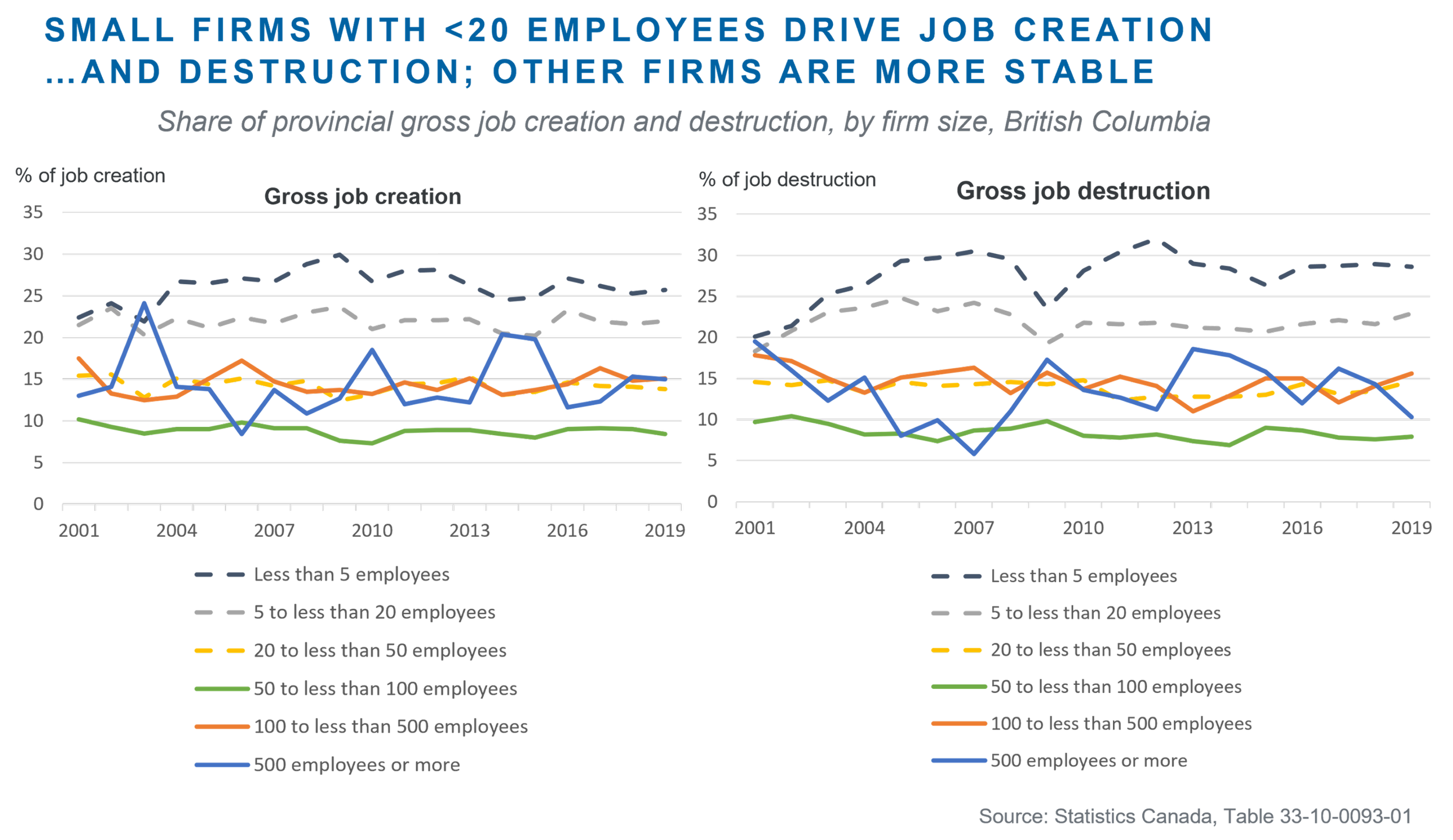

Job churn vs job stability

A stylised fact in labour economics is that there tends to be more job turnover or “churn” at very small firms. In B.C., very small firms with less than 5 employees and 5-19 employees are together responsible for about half of provincial job creation. However, they are also responsible for half of all jobs destroyed (Figure 3). Once a firm reaches 20 staff, the rate of job “churn” decreases markedly. All other firms, those with 20 or more employees, are responsible for the other half of provincial jobs created and destroyed.

Interestingly, firms with 50-100 employees have the least job “churn”. Could this be related to the corporate income tax regime? The federal-provincial statutory tax rate on corporate income more than doubles when businesses reach $500,000 of net income, so the data may be suggesting there is a sizable cluster of firms stuck around that prescribed level of business activity with little or no incentive to grow beyond it and no disincentive to shrink/exit.

Figure 3

B.C. firms are growing up

“Creative destruction” is the pathway to higher productivity and living standards. When firms must vigorously compete in product markets, and engage in international trade, they innovate and invest to survive. Successful firms scale up. Unsuccessful firms shrink before exiting the market. The process of creative destruction raises productivity and living standards across the economy, as freed-up capital, and labour shift from shrinking low-productivity firms to growing higher-productivity firms.BCBC’s 2017 policy paper laid out the evidence as to why large firms are critical to improving productivity and living standards. Relative to small firms, large firms tend to:

Invest proportionately more in capital equipment, intellectual property assets, technology, and economies of scale tooperate at higher levels of productivity (i.e., higher output or value-added per worker).

Compete in international markets and generate export earnings, thereby contributing to the province’s “economic base.”

Engage in research and development (R&D)– large firms are responsible for about half of R&D investment in Canada.

Pay higher wages – employee compensation at large firms is about 30% higher than at small firms, on average. This is because the benefits of capital investments, innovations, and economies of scale accrue to both workers and the firm’s owners.

Pay substantial taxes, including corporate income taxes, provincial sales tax, royalties, and other taxes that help fund public services. Moreover, because large firms pay higher wages than small firms, on average, and because B.C.’s personal income tax rates (PIT) are progressive, the typical large firm worker pays more in PIT than the typical small firm worker. At around 32% of total government revenue, PIT is important because it is the largest revenue item in the B.C. Budget. Thus, through the tax system, the above benefits are shared among British Columbians – even among those who do not work at such firms or hold an ownership stake in them.

B.C. has historically had an over-representation of very small firms relative to the province’s population (Finlayson and Peacock, 2017). The data presented here shows that over 2001-2019 employment opportunities increased at large firms and decreased at small firms, as a share of total provincial employment (and private sector employment). Prima facie, this is good news for British Columbians.

[1]

Canada’s Department of Industry, Science and Economic Development (ISED) defines a small business as 1-99 employees (excluding self-employed workers), medium-sized business as 100-499 employees, and large business as 500+ employees. In our firm, the definition of small business is quite broad. A firm with two employees is a materially different operation from one with 98. Therefore, we have chosen to show employment by firm size in greater detail as plotted in Figures 2 and 3.