Canada’s post-pandemic economic recovery was the 5th weakest in the OECD

Canada’s economy has generated little prosperity for the average Canadian over the past 8 years. Government forecasts indicate the economy is also expected to generate little or no prosperity over the next 8 years (see Williams 2023a).

The first step to managing any problem is to acknowledge that you have one. In contrast, the 2023 Federal Budget (page 5) claimed:

Canada’s economy is now 103 per cent the size it was before the pandemic, marking the fastest recovery of the last four recessions, and the second strongest recovery in the G7. Throughout 2022, our economy demonstrated sustained strength, with Canada posting the fastest growth in the G7 over the past year.[emphasis added]

Similarly, in the 2022 Fall Fiscal Update, the government claimed (page 27):

“There is no country better placed than Canada to weather the coming global economic slowdown and thrive in the years ahead.” [emphasis added]

The federal government’s decision to focus on GDP in its statements (i.e., “the size of the economic pie”), rather than GDP per capita (“everyone’s share of the economic pie”), is unfortunate. Over the past year, Canada’s real GDP grew by around 1%, but the population grew by 3% (1.2 million persons), so in per capita terms the economy became about 2% smaller. GDP growth is being juiced by the government’s pursuit of the fastest population growth since 1957-58. The 1957-58 episode followed two major global events, the Hungarian Revolution and Suez Crisis, whereas the current period entirely reflects domestic policy choices.

It’s true that when the population increases, GDP increases. But does the economy get any better in terms of people’s living standards? What happens to everyone’s share of the economic pie? To answer those questions, we need to focus on GDP per capita.

How did Canada’s economy perform prior to the pandemic?

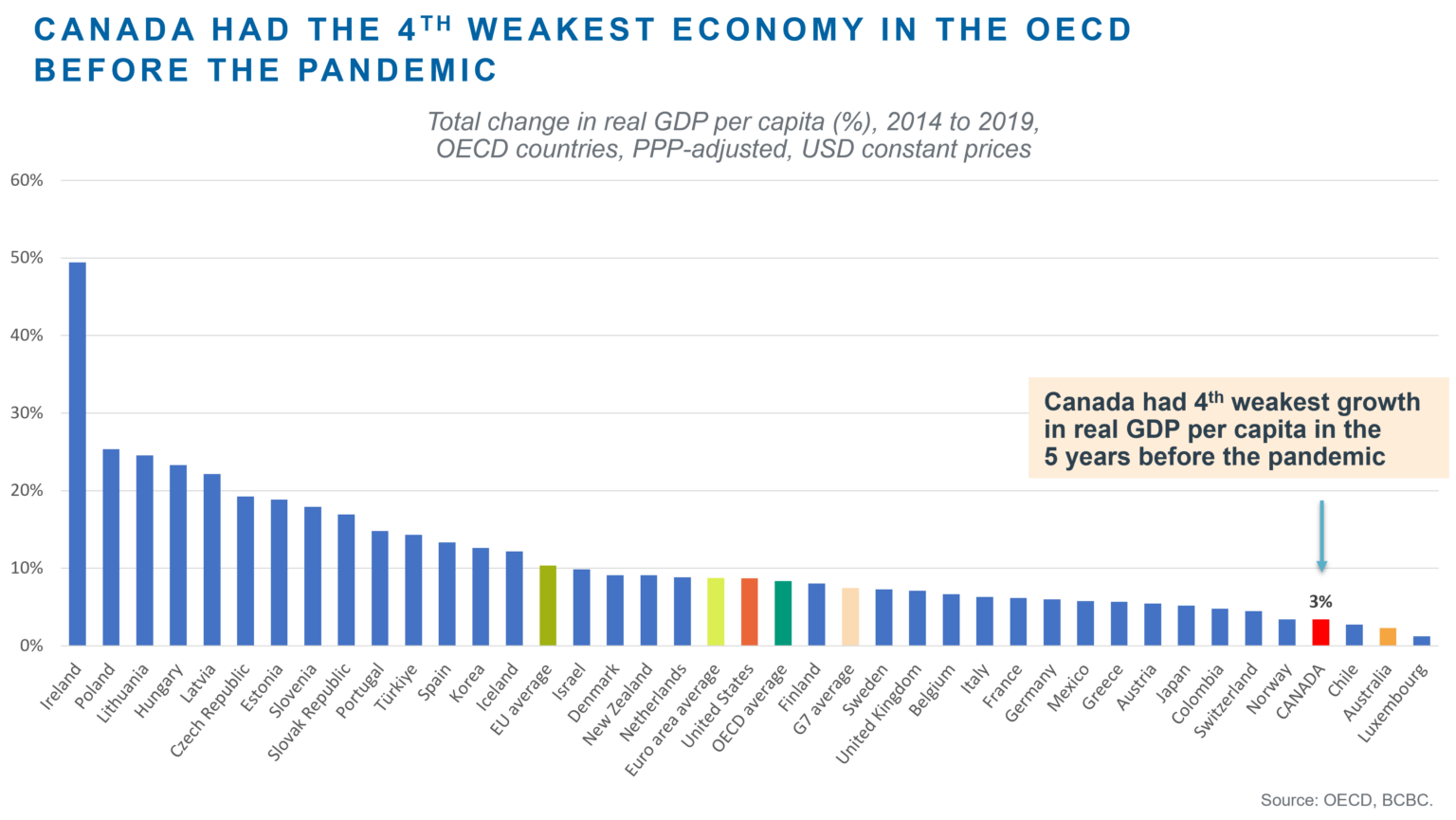

In the five years to 2019, Canada’s real GDP per capita grew by 3% (0.5% per annum). It was the 4th weakest performance out of 38 advanced countries (Figure 1). Canada lagged well behind the United States (9%), Euro area average (9%), OECD average (8%), and G7 average (7%).

Figure 1

How has Canada’s economy performed since the pandemic?

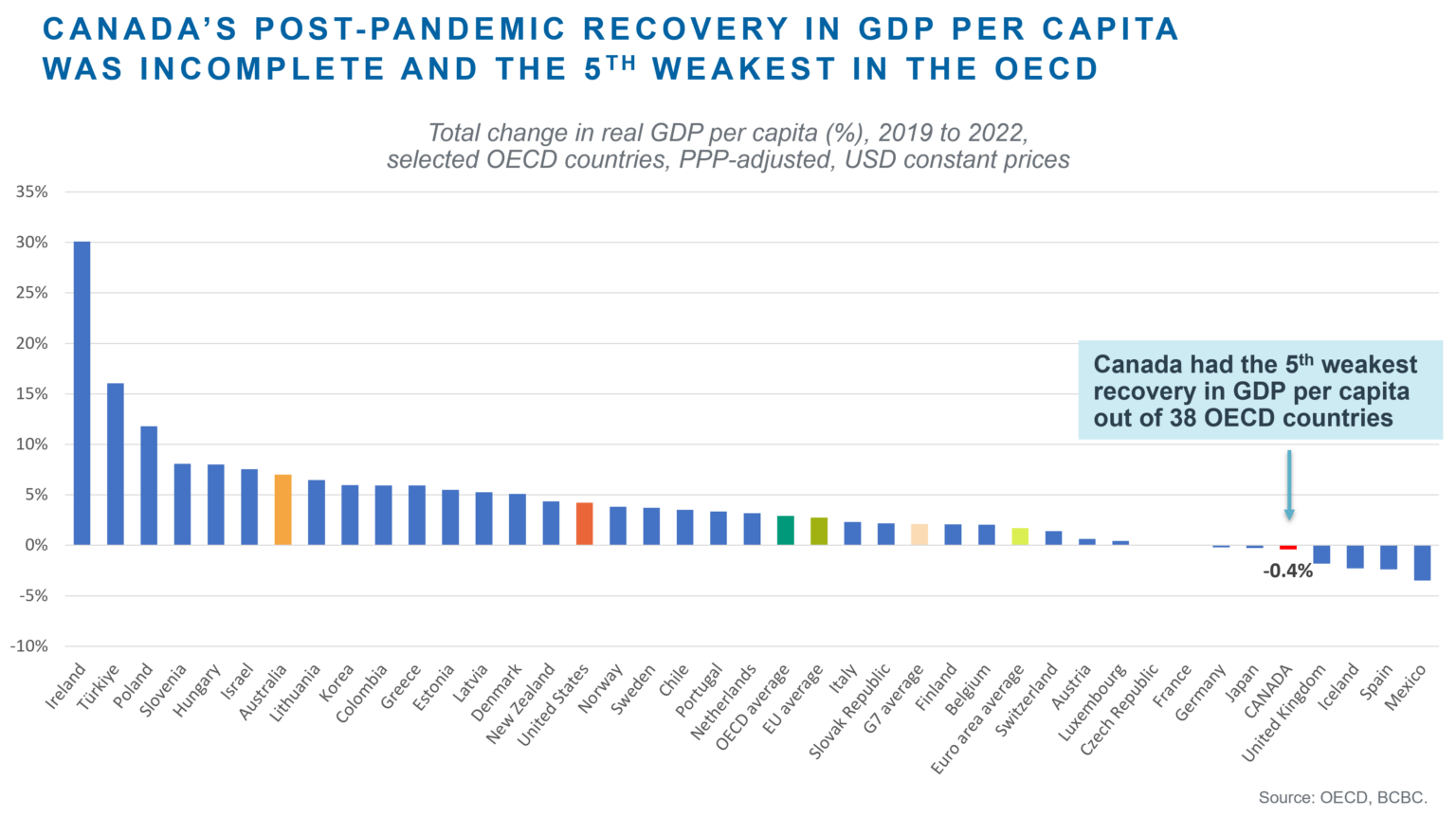

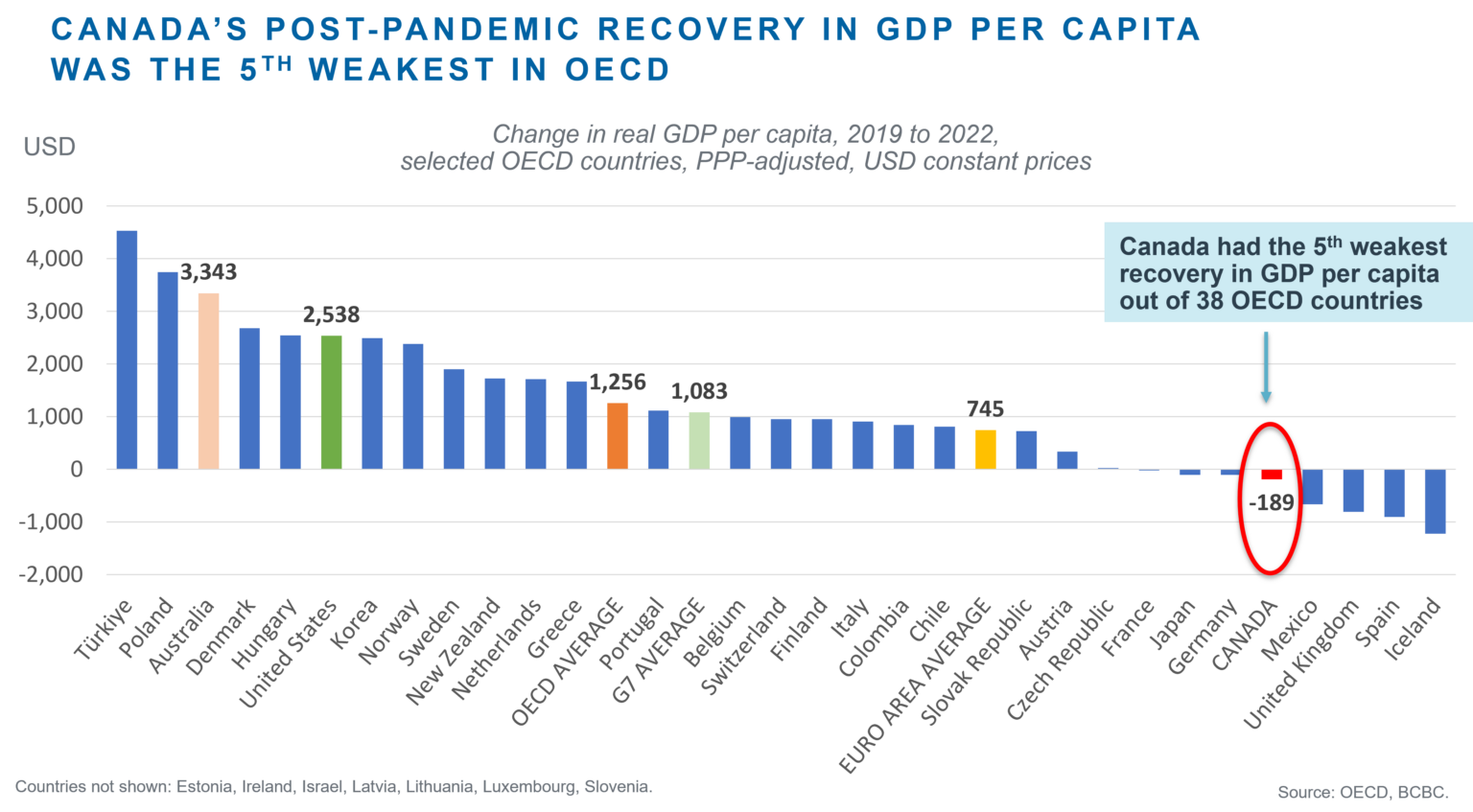

Canada is one of only eight advanced countries where real GDP per capita is lower than before the pandemic. For the change in real GDP per capita over 2019-22, Figure 2 shows percentage growth rates and Figure 3 shows growth in US dollars (adjusted for purchasing power parity, PPP, across countries).

Canada’s real GDP per capita was USD 200 (0.4%) lower in 2022 than in 2019. In contrast, it was USD 3,300 (7%) higher in Australia, USD 2,500 (4%) higher in the United States, USD 1,300 (3%) higher for the OECD average and USD 1,100 (2%) higher for the G7 average.

Canada’s post-pandemic recovery in real GDP per capita over 2019-22 was the fifth weakest out of 38 OECD countries. Only the economies of the United Kingdom, Iceland, Spain and Mexico have had weaker recoveries.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Immigration is not an economic panacea

Immigration, not productivity, is the centrepiece of the federal government's economic growth plan. However, the academic literature overwhelmingly finds that immigration levels have a neutral or negligible overall impact on a country’s living standards as measured by labour productivity, real wages, the employment rate, the age structure of the population or, crucially, GDP per capita.

There is a strong consensus on these points among Canada’s top labour market economists:

Professor Pierre Fortin (University of Quebec)

Professor Mikal Skuterud (University of Waterloo)

Associate Professor Matthew Doyle (University of Waterloo)

Professor David Green (University of British Columbia)

Professor W. Craig Riddell (University of British Columbia)

Professor Frances Woolley (Carleton University)

Professor Christopher Worswick (Carleton University)

The fact that immigration has an overall neutral effect on GDP per capita (i.e., on “everyone’s share of the economic pie”) in the long run means we need to look through the veneer of population growth to see what is happening to living standards. GDP per capita is a good metric for this.

Reality check

Unfortunately, the federal government’s economic statements tend to focus on GDP growth. In the current context, with turbocharged population growth and labour productivity falling, this is an unhelpful metric.

It is out of touch with the weak economy most families are facing:

Canada’s growth in GDP per person was the fourth-weakest in the OECD in the five years before the pandemic to 2019.

Canada is one of only eight advanced countries where average real incomes are lower than before the pandemic, as inflation outpaces growth in nominal incomes.

Canada’s recovery in real GDP per capita was the fifth-weakest in the OECD over 2019-22.

The OECD projects Canada will be the worst performing economy among the 38 advanced economies over both 2020-30 and 2030-60, with the lowest growth in real GDP per capita (see Williams, 2021).

Young and aspirational Canadians face 40 years of stagnation in average real incomes (Williams 2021). The principal reason is that Canada is expected to rank dead last among OECD countries for growth in labour productivity over most of 2020-60. Our workforce is less productive than workforces in peer countries (in terms of output per hour worked) because of relatively lower levels of non-residential capital investment per worker, lower levels of innovation and R&D, and because the average firm is less likely to export and produce output at scale.

Ignoring a problem does not make it go away

The federal government was so alarmed by Chart 28 of the 2022 Federal Budget (pages 25-26) – showing Canada dead last among 38 advanced countries for projected growth in real GDP per capita over 2020-60 – that it took bold and decisive action: by erasing any mention of this issue from its 2023 Federal Budget. The omission was not lost on columnist Andrew Coyne at the Globe and Mail.

Ignoring a problem does not make it go away. Canada’s structural problems need to be acknowledged (Williams (2023b)) and our economic policy mix needs rethinking (Williams and Finlayson (2023)).

Canada needs a prosperity-focused policy agenda focused on improving conditions for non-residential business investment, innovation, technology adoption and exports. With the Fall Economic Statement due in November, we encourage the federal government to take this opportunity to address these issues.