Federal and B.C. governments must improve their fiscal transparency

A new report by the C.D. Howe Institute assesses the fiscal transparency of the federal and provincial governments (Robson and Dahir, 2023). The authors examine governments’ budgets and financial statements from 2020 to 2023 and give annual letter grades on their overall fiscal transparency based on four criteria: timeliness; placement of key metrics; reliability and transparency of metrics; and comparability of metrics. This blog focuses on the results for the federal and B.C. governments, which are most relevant to British Columbians.

Why does fiscal transparency matter?

Fiscal accountability is crucial for the effective functioning of parliamentary democracies, as the authors eloquently explain (page 15):

Taxpayers’ and citizens’ ability to monitor, influence and react to legislators’ and government officials’ stewardship of public funds is fundamental to representative government. Legislators and officials should act in the interest of the people they represent, and if they are acting negligently or in their own interest, taxpayers and citizens need to know. Financial reports are key tools for monitoring governments’ performance of their fiduciary duties.

It is not about whether governments spend and tax too much or too little, whether they run surpluses or deficits, or whether their programs succeed or fail. It is about whether Canadians can get the information they need to form opinions on these issues and to correct any problems they discover. The letter grades in this report reflect our judgment about whether governments’ budgets, estimates and financial statements let legislators and voters understand governments’ fiscal plans and hold governments to account for fulfilling them.

Methodology

To develop their fiscal transparency scorecard, the authors put themselves in the mind of a non-expert reader of government budget plans and financial statements (e.g., a legislator, journalist or voter). The authors grade governments on several criteria:

Timeliness – fiscal documents should be released in a timely manner so that elected parliamentarians have full information to debate and make good decisions about tax and spending proposals.

Placement of key metrics – important numbers should be easy to find and identify in the documents. Readers should not have to wade through reams of “extraneous or potentially misleading material” (in other words, “puffery” or “spin”).

Reliable and transparent numbers – readers should be able to easily find consolidated revenues, consolidated expenses, and the budget surplus or deficit. Also, the accounts should have been signed off by the Auditor General without qualification. In other words, an independent, expert statutory officer is willing to certify that there is no “funny business” going on in the accounting.

Comparability of numbers – readers should be able to easily compare current budget statements with previous years’ financial statements.

Canada and B.C. governments have room for improvement on fiscal transparency

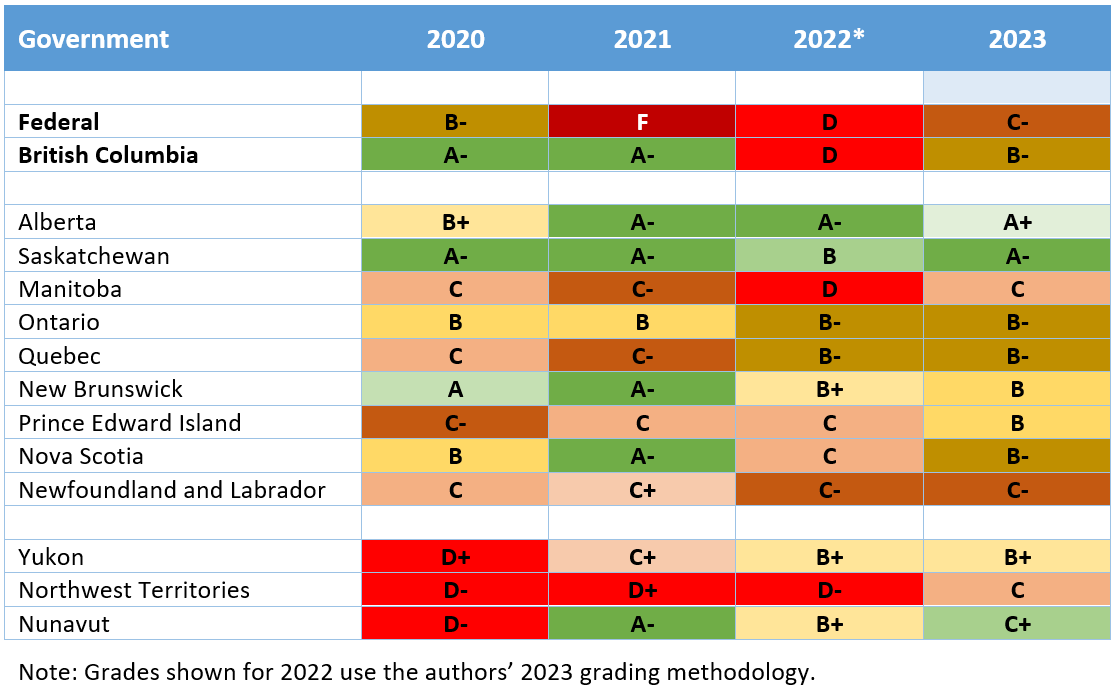

Before discussing this year’s results, it is important to recall that both the federal and British Columbia governments were at the back of the class in 2022, with both receiving failing grades of “D” (Table 1). Notably, the federal government received an even worse grade of “F” for 2021. This was mainly because, incredibly, it did not produce a budget for 2020/21. Yes, this was during the COVID-19 pandemic, but to our knowledge Canada was the only country in the world where the national government decided to skip producing a budget at all. This is shocking because the federal government is expected to show leadership in fiscal accountability, not drag down the class average through truancy.

In 2023, the good news is that the federal and B.C. governments modestly improved their fiscal transparency grade relative to 2022. Still, the federal government received a dismal grade of “C-”. It remains at the back of the class along with Newfoundland and Labrador. The B.C. government did better. It improved its grade to a “B-”. This puts B.C. about the middle of pack among the provinces and territories. Nonetheless, the federal and B.C. governments remain a long way behind the best-in-class provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan who received exemplary grades of “A+” and “A-”.

Table 1: Canada and B.C. governments have room for improvement on fiscal transparency

Overall grade for timeliness and transparency of governments’ fiscal reporting

Source: Robson and Dahir, 2023.

Report card comments for Canada and B.C.

The authors of the C.D. Howe paper offered the following comments on the federal government’s report card for 2023 (Robson and Dahir, 2023, page 14):

The federal government was the only government to provide a deadline for committee consideration of its main estimates. It ranked below average because it released its budget after the start of the fiscal year, it failed to highlight consolidated expenses in both its budget and public accounts, it buried key figures in a budget appendix, it used different accounting for its budget and estimates and it had a relatively large below-the-line adjustment. [emphasis added]

The authors wrote the following comments on the B.C. government’s report card for 2023 (Robson and Dahir, 2023, pages 9, 14 and 17):

In the B tier were Yukon (B+), Prince Edward Island (B), New Brunswick (B), Nova Scotia (B–),Quebec (B–), Ontario (B–) and British Colombia (B–).

British Columbia presented timely budgets and estimates, but its budget did not consolidate expenses, and qualifications by its auditor represented a significant percentage of its expenses [emphasis added; note, the auditor sought more disclosure about contractual obligations].

British Columbia was an A– performer in the past, but has slipped lately. The size of thediscrepancy flagged by its auditor general is an ongoing problem, as is its below-the-line adjustment. Its 2022 budget did not highlight consolidated expenses, and featured a large contingency reserve, which lowered its grade this year.

For the class valedictorian, Alberta’s report card for 2023 reads as follows (Robson and Dahir, 2023, pages 9 and 17):

Topping the class was Alberta, with an A+ grade, followed by Saskatchewan with A–. Both released their public accounts within 90 days of year-end. Both presented the key numbers early in their budgets and public accounts, and used consistent accounting in those documents as well as in their estimates. Both tabled their budgets and estimates simultaneously before the start of the fiscal year, and published in-year updates with consistent budget comparisons.[emphasis added]

Alberta has been a solid performer since 2015, when it stopped showing multiple balance figures in its budgets. Its timely budget release helped it top the class this year. Provincial legislation requires tabling Alberta’s budget in February, a deadline it achieved in fiscal year 2022/23.

How can governments improve their fiscal transparency?

Robson and Dahir (2023) outline several principles that governments should follow to improve their fiscal transparency:

Ensure budget documents and financial statements reflect public sector accounting standards (PSAS), with consolidated revenues, expenses, surpluses or deficits, and with tables and explanations for changes from past results and deviations from past projections.

Budgets should be released before, not after, the start of the fiscal year. They argue, “It is an affront to accountability to ask legislatures to approve a plan after money has already been spent” (Robson and Dahir (2023): p20). The authors cite the egregious failure of the federal government to present a budget at all in 2020/21 notwithstanding wartime levels of expenditures. The authors recommend there be a legislated budget date for senior governments, preferably before the end of January.

Estimates should reconcile with budget documents and receive timely consideration. Fiscal estimates should be shown on the same accounting basis, and the same aggregation basis, in all budget documents and financial statements, so that changes or discrepancies can be readily identified. Also,the authors recommend governments release their main estimates at the same time as their budgets, as is the practice in Australia and New Zealand.

Key numbers should be accessible and recognisable. Governments should provide the key numbers up front so readers can easily find them. They should declutter their budget documents and avoid burying important numbers deep in rambling text.

Year-end results should be timely. The federal government’s tabling of its public accounts up to 9 months later is unacceptably tardy when the fiscal year ends on March 31. By contrast in Alberta, public accounts must be tabled by June 30! The authors argue that given current technology there is no reason for such lengthy delays in producing public accounts. They propose that senior governments be required to table their public accounts within 90 days of the end of the fiscal year (i.e. by the end of June) or, failing that, by the end of September at the latest.

Legislators should review the Public Accounts. Parliamentary standing committees should scrutinize public accounts for government effectiveness and efficiency, and raise concerns with auditors general.

BCBC’s views about federal and provincial fiscal transparency

BCBC shares the C.D. Howe Institute’s concerns about the quality of the federal government’s budgeting. Whereas it should be a leader, the federal government’s fiscal transparency has significantly deteriorated over time. Unfortunately, it is the level of government most likely to bury key numbers in long, convoluted and rambling budget documents. The federal government tends to table its budget after the start of the fiscal year (April 1). It also tends to release its public accounts for the fiscal year (which ends on March 31) up to nine months later (in November or December). These delays are unjustifiable, and they could be interpreted as emblematic of a general attitude to thwart proper and timely scrutiny of federal spending.

The B.C. government’s budget documents are clearer, shorter and better structured than the federal government’s. The provincial budget is tabled in February, before the start of the fiscal year, unlike the federal government. Thus, the “B-” grade for 2023 seems fair. That said, B.C. has room for improvement. B.C. consistently received “A” grades for fiscal transparency in the past. We see no reason B.C. should not aim to match Alberta in best practice for being fiscally transparent with its citizens.

In terms of specific practices that could be improved (beyond what has been highlighted by the C.D. Howe Institute above), we believe B.C.’s use of contingent reserves is becoming excessive and political. Contingencies are funds set aside for unforeseen events. They should be reasonable and modest. At the end of the year, any unused reserves should be used to pay down government debt. It creates a moral hazard for them to be directed toward new spending at the Premier or Finance Minister’s whim – long after that year’s budget has been scrutinized by the legislature. To be candid, the B.C. government’s recent use of unspent contingent reserves for new spending risks them being viewed as an end-of-year slush fund. That should not be their purpose. It is especially problematic when B.C. is running the largest deficit relative to the size of its economy of any province and should be working to establish fiscal targets and anchors.

We would also suggest that consultations on the provincial budget return to the autumn rather than in the spring months. As it did in the past, this provides better opportunities for stakeholders to provide meaningful and relevant input and to give the consultations greater prominence. Finally, after budget lockups (i.e., after all budget materials have been made public), stakeholders and media attending the lockup should be allowed to interact and speak freely without partitioning or oversight by government minders.

Conclusion

The last word should go to the authors (Robson and Dahir, 2023, p22):

Governments play a massive role in the Canadian economy and in the lives of Canadians. The chains of accountability that link citizens’ wishes, through their elected representatives, with the officials who tax, regulate and serve them are long and complicated, and transparency and accountability in fiscal policy are essential.

An intelligent and motivated, but non-expert, citizen seeking to understand a government’s current fiscal situation and plans should be able, quickly and confidently, to find the key figures in budgets, estimates and public accounts. That citizen should be able readily to see what that government plans to do before the year starts, and to compare that with what it did shortly after the year has ended

As this report card shows, governments that do not meet these standards could make some straightforward changes to improve. The grades of the top performers reflect consolidated financial statements consistent with PSAS [Public Sector Accounting Standards], and budgets, estimates and interim reports prepared on the same basis. All governments can do that. They also reflect presentations that make the key numbers readily accessible early in the relevant documents. All governments can do that. And they reflect timely presentations: budgets presented before the fiscal year starts and public accounts tabled shortly after fiscal year-end. All governments can do that.

References

Robson, W. B. P. and N. Dahir. 2023. “The ABCs of fiscal accountability: The report card for Canada’s senior governments, 2023,” C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary no. 646, October 24.