Going nowhere: The stagnation of real incomes in Canada and B.C.

BCBC analysis published in December 2021 highlighted that the OECD projects Canada will be the worst performing economy out of 38 advanced countries over both 2020-30 and 2030-60, with the lowest growth in real GDP per capita (Williams 2021). The principal reason for this sobering forecast is Canada’s weak growth in labour productivity (i.e., value-added per unit of labour input). In other words, other developed countries are expected to eclipse Canada in expanding business investment per worker, talent and skills per worker, innovation and R&D per worker, and in exporting and producing output at scale.

Our 2021 analysis has received considerable attention:

the 2022 Federal Budget (see pages 25-26 and chart 28);

several columns in the Globe and Mail by:

Williams and Finlayson, February 2022;

Patrick Brethour, December 2021 and February 2022;

Andrew Coyne, April 2022 and March 2023;

Matt Lundy April 2023;

a Toronto Sun editorial in April 2022;

a speech by former Federal Finance Minister, Bill Morneau, in June 2022 (see Kirby, 2022);

comments by former Blackberry-CEO, Jim Balsillie (see Kirby, January 2023);

the Financial Post (Diane Francis, January 2023);

the National Post (Sabrina Maddeaux, April 2022);

the Vancouver Sun (Douglas Todd, May 2022);

Macleans Magazine’s Charts to Watch in 2022 (Markusoff, December 2021); and

two radio interviews with Simi Sara (CKNW) and Adam Stirling (iHeart).

Below are the key charts from Williams (2021) showing the OECD’s projections for growth in real GDP per capita among advanced countries over 2020-30 (Figure 1) and 2030-60 (Figure 2). Canada is expected to run dead last in both periods.

Figure 1

Figure 2

What does the latest data show for Canada?

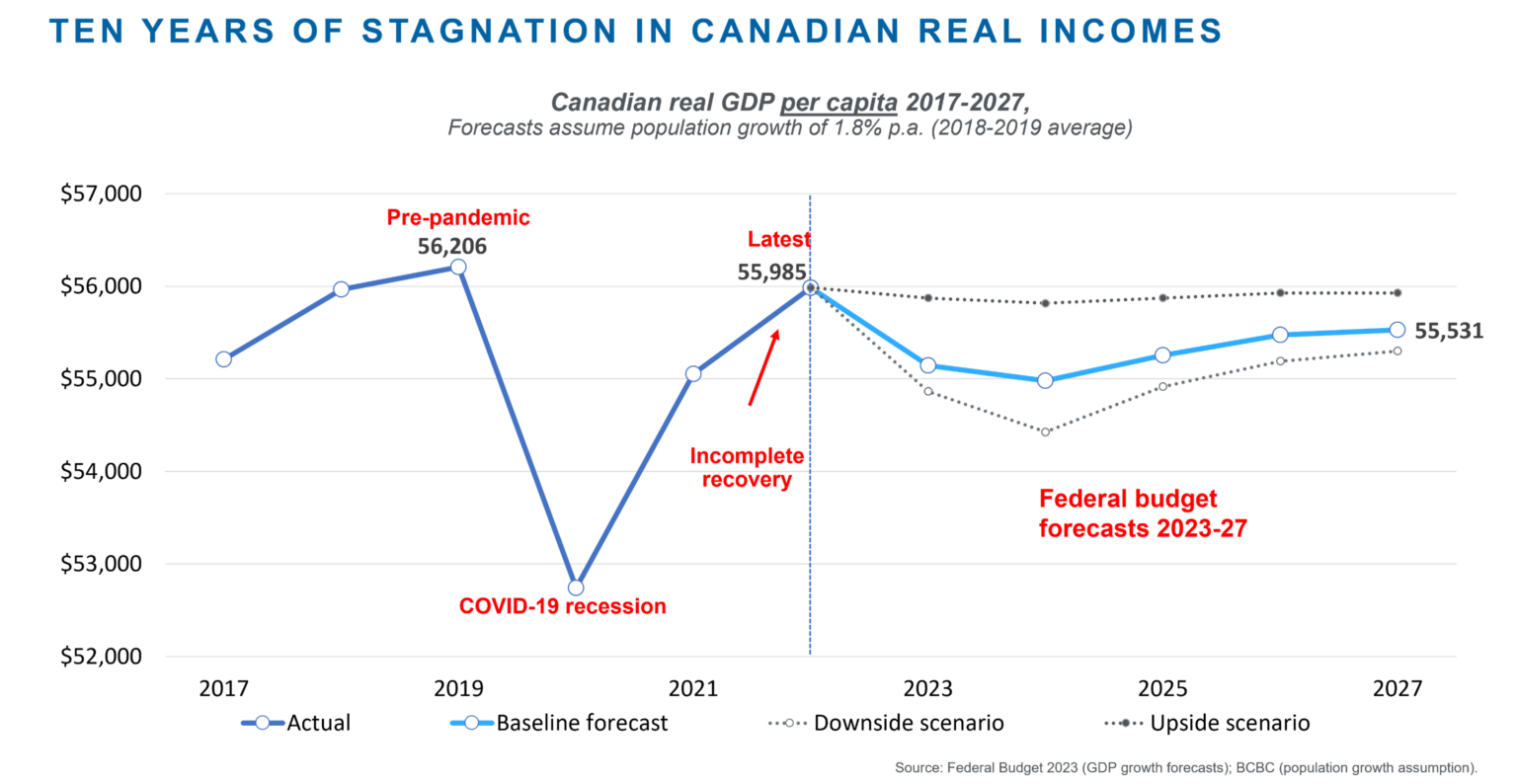

The latest data shows Canada is on track for a “lost decade” in average real income growth. Figure 1 shows Canadian real GDP per capita over 2017-22 (actual) and 2023-27 (projected). GDP per capita was $55,211 in 2017 and peaked at $56,206 in 2019. It collapsed to $52,741 in 2020 during the pandemic. Since the pandemic, Canada’sGDP per capita has only partially recovered to $55,985 in 2022 – still 0.4% below its 2019 level. Canada is one of the few advanced countries not to have recovered its pre-pandemic level of GDP per capita.

Average real incomes are also expected to stagnate in the years ahead. To generate forecasts for GDP per capita, we took the latest (2023) Federal Budget forecasts for GDP growth over 2023-27, and then subtracted an assumed population growth rate of 1.8% per annum. (The latter was the pre-pandemic annual rate of population growth over 2018-19. It is, however, well below the blistering population growth rate of 2.7% recorded for 2022 – which could imply our estimates for GDP per capita should be even lower.) Under these assumptions, the level ofCanadianGDP per capita is expected to reach $55,531 in 2027, which is 1.2% below its pre-pandemic level in 2019, and only 0.6% above its level in 2017.

Figure 3

What does the latest data show for B.C.?

B.C.’s real GDP per capita peaked at $53,769 in 2019 before dropping to $51,563 during the pandemic. Unlike Canada, B.C.’s GDP per capita did fully recover its pre-pandemic level, reaching an estimated $54,600 in 2022. Nonetheless, real incomes in B.C. are still around 2.5% below the national average (which, as noted above, has less than fully recovered from the pandemic).

Looking ahead, the 2023 B.C. Budget provides forecasts for provincial real GDP per capita over 2023-25. Average real incomes are expected to fall in 2023 and then stagnate across the rest of the forecast horizon. By 2025, B.C. GDP per capita is expected to be $53,616, which is 0.3% below its 2019 level, and 1.6% below its 2022 level.

Figure 4

Conclusion

Young Canadians entering the workforce today face 40 years of near-stagnant growth in average real incomes, according to the aforementioned OECD projections. The latest data shown in Figures 3 and 4 above indicate that Canada and B.C. are on track to deliver that dismal outcome.

Thus far, the response from policymakers has been to ignore the issue and to double-down on the demonstrably “prosperity-free” growth strategies favoured prior to the pandemic (see Williams, 2020). For example, the Trudeau government was so alarmed by Chart 28 of the 2022 Federal Budget (pages 25-26) – showing Canada dead last in the OECD for growth in real GDP per capita over 2020-60 – that it took bold and decisive action: it scrubbed any mention of the issue from its 2023 Federal Budget. The omission was not lost on columnist Andrew Coyne in the Globe and Mail.

Federal and provincial policymakers should address several structural issues that will have serious implications for future living standards (see Williams, 2023). This will require political leadership and technical expertise. If they are unwilling to do so, then at the very least, they should be clear with Canadians as to how they intend to manage the stagnation in average real incomes (in absolute terms) and the decline in average living standards relative to all other advanced OECD countries.