Low productivity growth is holding back Canadians' pay growth

Productivity and Pay in Canada: Growing Together, Only Slower than Ever, authored by Dr. David Williams, BCBC's Vice President of Policy, is the lead article in the Spring 2021 edition of the International Productivity Monitor, a peer-reviewed journal published by Canada's Centre for the Study of Living Standards and the Productivity Institute of the United Kingdom.

This month’s Policy Perspectives provides a summary of the key findings of the major paper which examines the relationship between growth in real output per hour worked (labour productivity) and real total labour compensation per hour worked (pay) over six business cycles, from 1961 to 2019.

As found in Dr. Williams’ research, when both concepts are carefully measured, pay and productivity in Canada are shown to have broadly kept pace with each other over both the long run and the most recent business cycle from 2008-2019. Fundamentally, Canada’s serially weak productivity growth, the general stability of the labour share (adjusted for depreciation and output-based taxes), and the lack of further gains in labour’s terms of trade after 2008 mean there is little to drive long term growth in real pay.

Click here for the full research paper

Highlights

A populist narrative goes like this: policymakers can ignore productivity growth because the link between people’s pay and a country’s productivity is broken; workers are receiving a shrinking share of the economic pie; and overall income inequality is rising. However, a careful look at the data for Canada shows that none of these claims are correct.

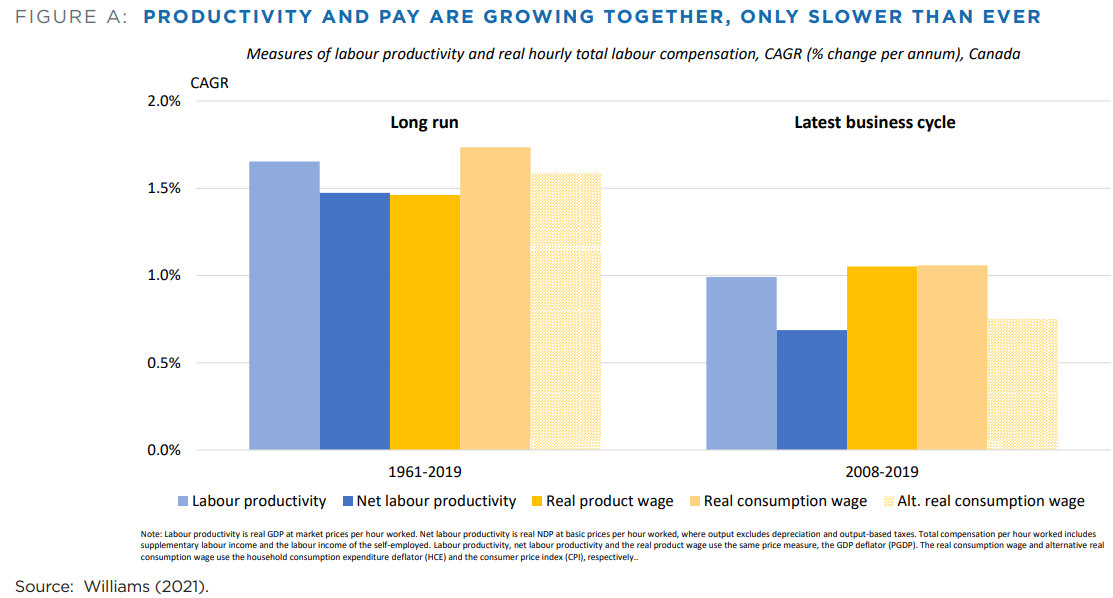

A peer-reviewed study by this author finds that over the long run from 1961-2019, growth in productivity and real average pay in Canada are broadly in line at around 1.5-1.7% per annum (Figure A).

The period since 2000 has seen Canada’s weakest productivity growth since records began in 1961. Initially, during the 2000-08 business cycle, the impact of the productivity growth slowdown on workers’ pay growth was ameliorated by some extraordinary – but temporary – relative price shifts. As China opened to the world, Canada’s resource-based economy benefited from soaring commodity prices, while cheap import prices boosted consumers’ purchasing power.

During the 2008-19 business cycle, the chickens came home to roost. There were no further fortuitous terms of trade shifts. Regardless of price measure, real pay growth slowed to around 1% per annum — broadly in line with the rate of labour productivity growth. Canada’s productivity growth problem was laid bare (Figure A).

Canada’s productivity growth performance ranks 21st out of 23 OECD countries over 1970-2000 and 25th out of 36 OECD countries over 2000-19. By 2019, on a purchasing power parity basis, real output per hour worked in Canada was about 27% lower than the United States, 21-22% lower than France and Germany, and 10% lower than the United Kingdom.

Had Canada’s productivity growth rate after 2000 matched the average for the members countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the average Canadian’s pay would be $2,900 higher in 2019.

Had Canada’s productivity growth after 2000 matched its own performance from 1961 to 2000, the average Canadian’s pay would be around $13,550 per annum higher in 2019.

International studies show that innovation diffusion slowed among firms after 2000, with the most likely culprits being regulatory impediments on competition and the reallocation of labour and capital to best use. For Canada since 2000, in terms of output per hour of labour input, non-leading firms have fallen further behind the country’s leading companies, while Canada’s most productive businesses have lost ground to leading global firms.

The good news is that there is ample scope for productivity “catch up”. Canada can raise productivity – and therefore real pay and living standards – through the widespread adoption of best practices and technologies already deployed by leading countries and firms.

Canadian policy discussions on economic growth tend to be overwhelmingly preoccupied with increasing GDP by expanding the labour supply. Increases in immigration, population and labour supply increase GDP, but they have negligible impact on GDP per capita. Furthermore, they do not materially alter the age structure of the population over time.

In contrast, higher productivity has the advantage of raising workers’ real incomes and GDP per capita. Thus, an economic growth strategy centred on raising productivity growth would be a better strategy than one focused on expanding the labour supply — because it would actually generate the resources to support retired workers and fund enhancements to Canada’s social safety net.

Curing the productivity-related maladies that have long weighed on Canada’s economic performance will require governments to review the structural policy settings that encourage or discourage product market competition and innovation diffusion, business dynamism and creative destruction, resource reallocation, and private sector investment in capital, skills and scale.

Productivity growth matters. Canadians should be concerned about the country’s serially low productivity growth because it leads to low real pay growth. Canada needs an institutional and policy framework that creates better conditions for economy-wide productivity gains.