Statistics Canada adopts BCBC’s proposed change to Canada’s Consumer Price Index

Overview

Canada’s consumer price index (CPI) significantly underestimates increases in mortgage interest costs for homeowners by underestimating growth in outstanding mortgage debt. In April 2018, BCBC advocated for a change to the CPI by incorporating growth in established house prices – instead of only new house prices – into the CPI's mortgage interest cost index (MICI). The good news is that Statistics Canada implemented BCBC’s proposal in February 2021.Our original 2018 article is available here: How do house prices affect the consumer price index? A 2021 interview with the Globe and Mail on the change is here.The CPI is important because it is used by businesses and workers as an informal guide in wage negotiations, by governments to adjust tax brackets and transfer payments, and by the Bank of Canada as a target for monetary policy. This article explains the recent change to the CPI and why it matters.

Background: Mortgage interest costs in the CPI

Shelter is the largest component of the CPI, with a weight of over one-quarter. There are three main types of shelter costs in the CPI:

utilities costs (water, fuel and electricity prices);

rented accommodation costs (market rents adjusted for constant amenities and quality); and

owned accommodation costs paid by homeowners.

For owned accommodation costs, Statistics Canada treats homeowners as “landlords” who are assumed to rent the property to themselves. The CPI tracks six “landlord-like” costs incurred by homeowners:

mortgage interest costs (for primary residences only, excluding secondary properties);

municipal property taxes;

home and mortgage insurance costs;

home replacement costs (depreciation of the structure)[1];

maintenance and repair costs; and

other expenses.

Growth in the mortgage interest cost index (MICI) is the product of two things:

changes in average interest rates – Statistics Canada uses an average of market interest rates for owner-occupied mortgages over the past 60 months, because 5 years is the typical “term” or refinancing period of Canadian mortgages; and

changes in average mortgage principal outstanding – Statistics Canada uses an average of the amount of mortgage debt outstanding over the past 300 months, because 25 years is the typical “amortization” or lifespan of a Canadian mortgage. Growth in mortgage debt outstanding is determined by growth in nominal house prices, specifically, the new house price index (NHPI, including both structures and land). NHPI measures contractor’s selling prices for new dwellings collected from builders in 27 census metropolitan areas (CMAs) across Canada.

How much have mortgage sizes increased over time?

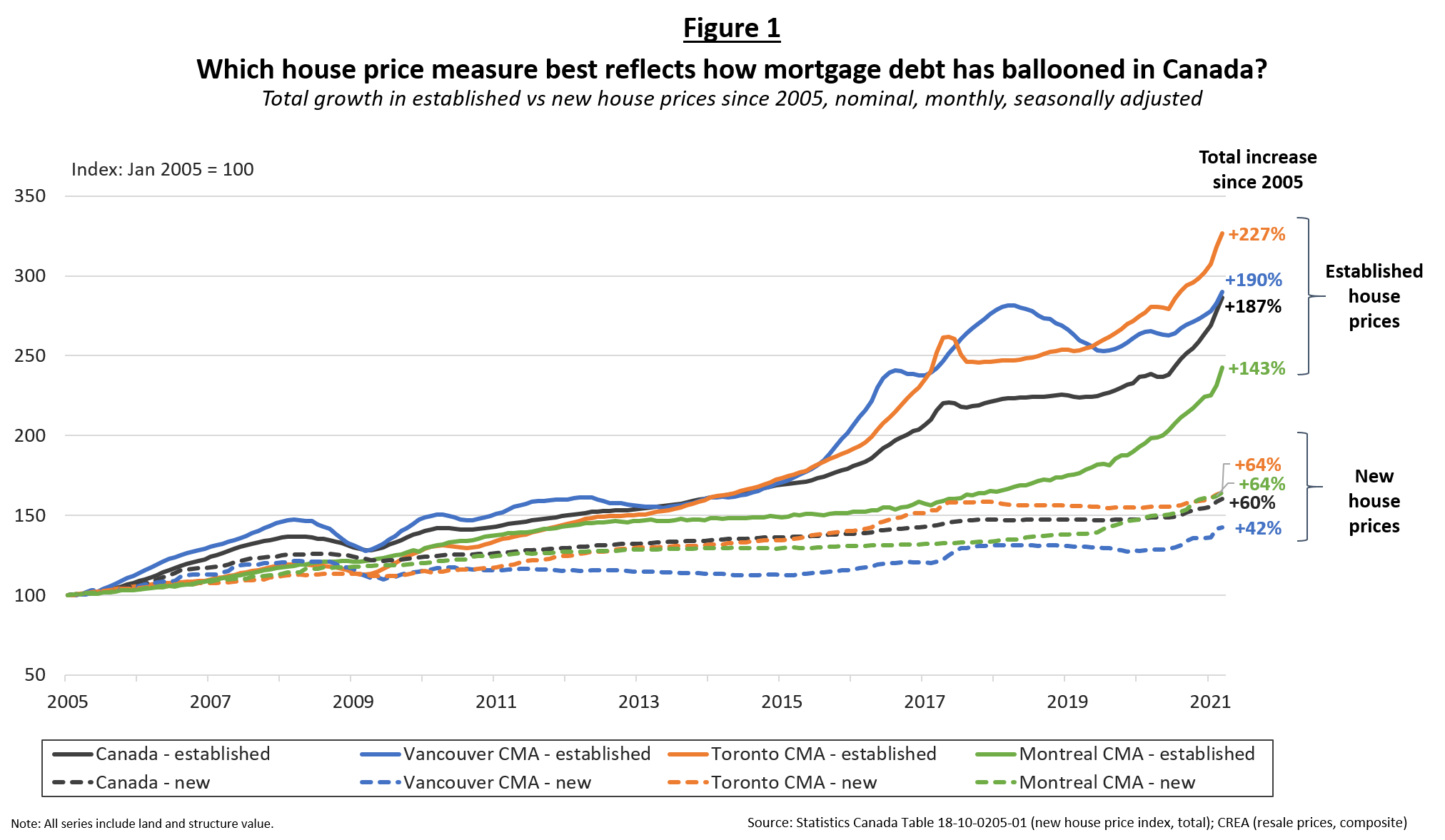

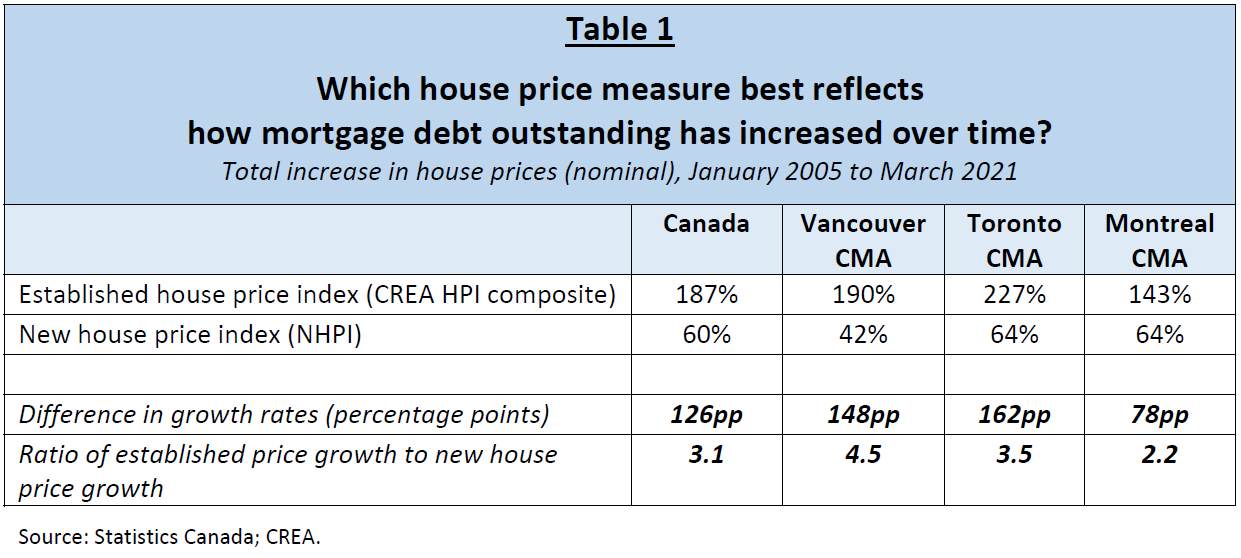

It is well known that Canadian households have borrowed liberally over the past two decades. Canada has the world’s 5th most indebted household sector as at the third quarter of 2020, with household debt to GDP of over 110%, (see Williams, 2021). Much of that increased indebtedness reflects larger mortgage sizes per borrower. However, the mortgage interest cost index (MICI) in the CPI did not reflect that reality.Most Canadian home buyers obtain and pay interest on mortgages for establishedhomes. The price of established homes (and the mortgage qualifying criteria set by banks and government policy) determine the size of the mortgage on which interest is charged. However, MICI assumed that all mortgages were for newly constructed homes. In Canada's largest cities, where roughly one-third of the country’s population live, established house prices have risen two to five timesmore than new house prices since 2005 (Figure 1 and Table 1). Nationally, established house price growth has been triple the rate of new house price growth since 2005. Note that all series include land and structure values. A future blog will explore the reasons why established house prices have grown so much faster than new house prices.

How much in mortgage interest are Canadian homeowners really paying?

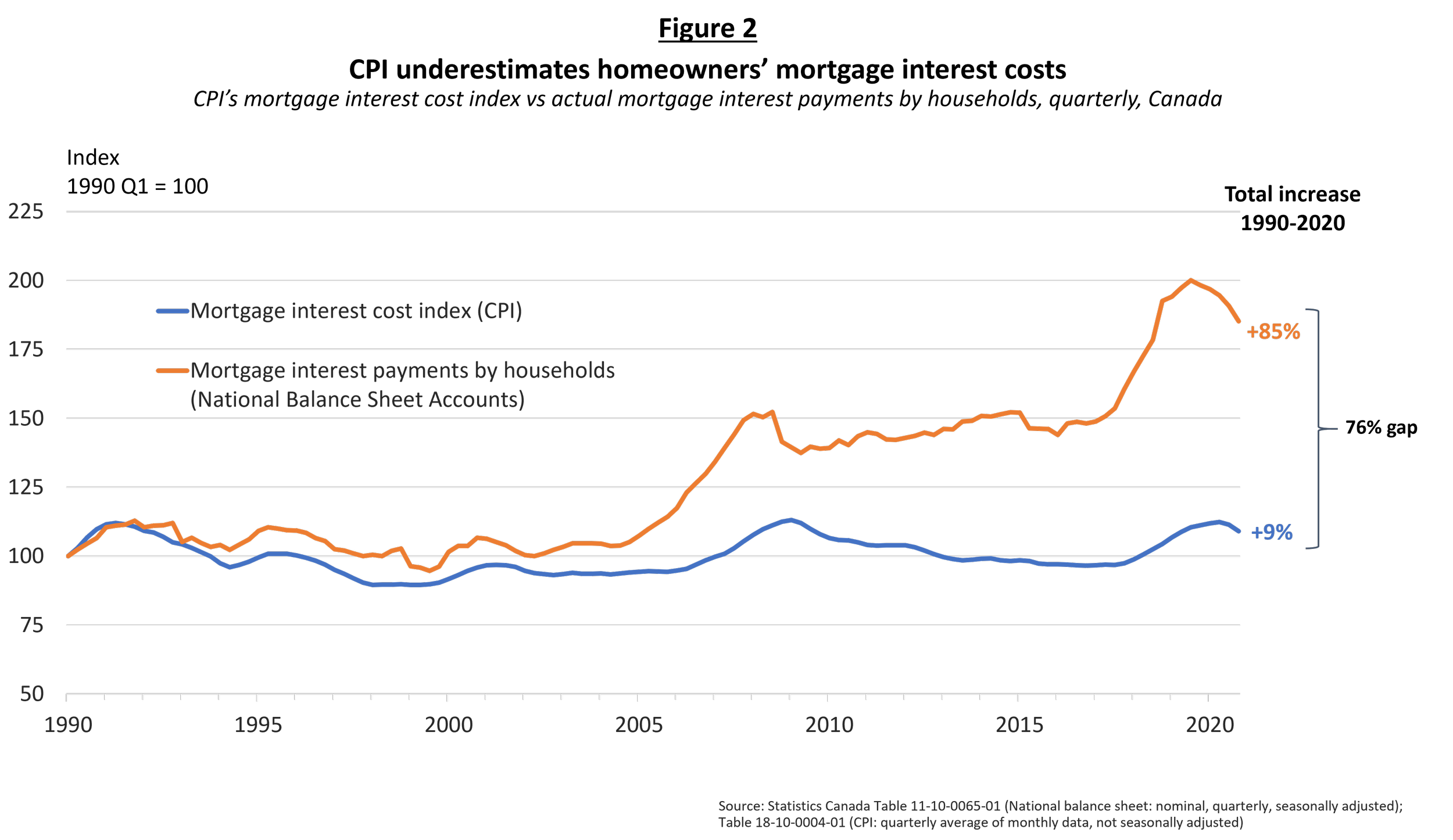

Notwithstanding the decline in mortgage interest rates over the past two decades, MICI has been underestimating mortgage interest costs because growth in mortgage sizeswas tied solely to new house price growth (while ignoring established house price growth). The disconnect can be seen by comparing growth in the CPI’s MICI with growth in households’ actual mortgage interest payments over time. From January 1990 to March 2021, the MICI increased by a meagre 9%. By comparison, national balance sheet data show households’ actual nominal mortgage interest payments rose by 85% over the same period (Figure 2). The difference between the two series is enormous, 76%, and is due to MICI underestimating growth in mortgage sizes. The corollary is that the CPI appears to have been systematically and significantly underestimating growth in homeowners’ mortgage interest costs.

What change did Statistics Canada make to the measurement of mortgage interest costs in the CPI?

In February 2021, Statistics Canada changed how growth in mortgage sizes is tracked in the MICI (see towards the bottom of the page in Statistics Canada, 2021). The change is in line with BCBC’s 2018 proposal. Henceforth, in tracking growth in mortgage principal outstanding in six major CMAs (Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Calgary, Vancouver and Victoria), Statistics Canada will put approximately two-thirds of the weight on established house price growth (previously 0% weight) and one-third of the weight on growth in new house price growth (previously 100%). For the remaining 21 CMAs, Statistics Canada lacks data on resale home prices and so will continue to put 100% weight on NHPI.

Conclusion

Canadian homeowners’ mortgage interest costs have been systematically and significantly underestimated in the CPI. This is important because the CPI is used as a guide in decisions made by businesses, workers, governments, and Canada’s central bank. The change in the way Statistics Canada calculates mortgage interest costs in the CPI – linking growth in mortgage sizes to established house price inflation instead of only new house price inflation – is a positive step towards developing a CPI that better reflects the rising costs of home ownership in Canada. Future blogs will look at some of the other aspects around the measurement of shelter costs in Canada’s CPI.

Further reading:

Lundy, M. and M. Rendell. 2021. “Why inflation numbers fail to capture Canada’s red-hot housing market?” Globe and Mail, May 10.Statistics Canada. 2021. Technical supplement for the February 2021 Consumer Price Index. Price Analytical Series, Catalogue no. 62F0014M, March 17.Statistics Canada. 2019. “The Canadian consumer price index reference paper.” Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 62-553-X.Statistics Canada, 2015. “The Canadian consumer price index reference paper: Chapter 10 – Treatment of owned accommodation and seasonal products.” Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 62-553-X (archived).Williams, D. 2018. “How do house prices affect the consumer price index?” Insights, Business Council of British Columbia, April 24.[1] Depreciation costs are imputed at 1.5% of the market value of owner-occupied residential structures in the CPI basket reference year. Changes in market value are tied to the new house price index for structures only (i.e. NHPI excluding land).