Canada’s 1m job vacancies are mostly in entry-level, low-wage positions

Ottawa is abuzz these days with talk of Canada’s “labour shortages.” Overheated economies tend to feature strong labour demand and upward pressure on wages for jobs that are marginally economically viable. But before looking at job vacancy data in more detail, let’s first define what a labour shortage is.

What is a labour shortage?

A labour shortage is defined as a job than cannot be filled at the current wage. How many vacancies and their duration are relevant factors to consider, but it’s most important not to forget the last part of that sentence, “at the current wage.” In a market economy, employers are free to adjust the wage they offer so long as wages are above the minimum wage. Similarly, workers are free to adjust the wage they are willing to work for. For example, a worker might decide to shift from a low-paying occupation, business or industry to a higher-paying occupation, business and industry. This “price mechanism” ensures the economy is always allocating scarce resources (labour) to their most productive use. It also encourages workers and businesses to invest in skills, capital and technology. Over time, that process makes our whole economy better off.

If an employer can’t afford to pay a higher wage to attract or retain staff, it creates a strong incentive to invest in capital equipment and technology to automate the activity, or to shift into higher value-added activities to make better use of the labour, and to scale back less profitable activities. Some current businesses might struggle to pay the higher wage that more productive firms, perhaps producing an entirely different or better good or service, can afford.

Federal and provincial policymakers need not be afraid of competition in labour markets or product markets. Competition is the beating heart of a vibrant economy. Schumpeterian economic growth, also known as “creative destruction,” is how economies become more productive over time and how societies improve overall living standards for their citizens.Want to interfere with the market mechanism? Then be prepared, as a country, to have labour not put to its most productive use. Low real wage growth is sure to follow.

Concerned about generalised labour shortages, and generalised consumer price inflation, because the economy is overheated? Then policymakers should be focused on tightening fiscal and monetary policy settings until demand for goods, services and labour are brought into balance with supply.

Where are Canada’s 1 million job vacancies?

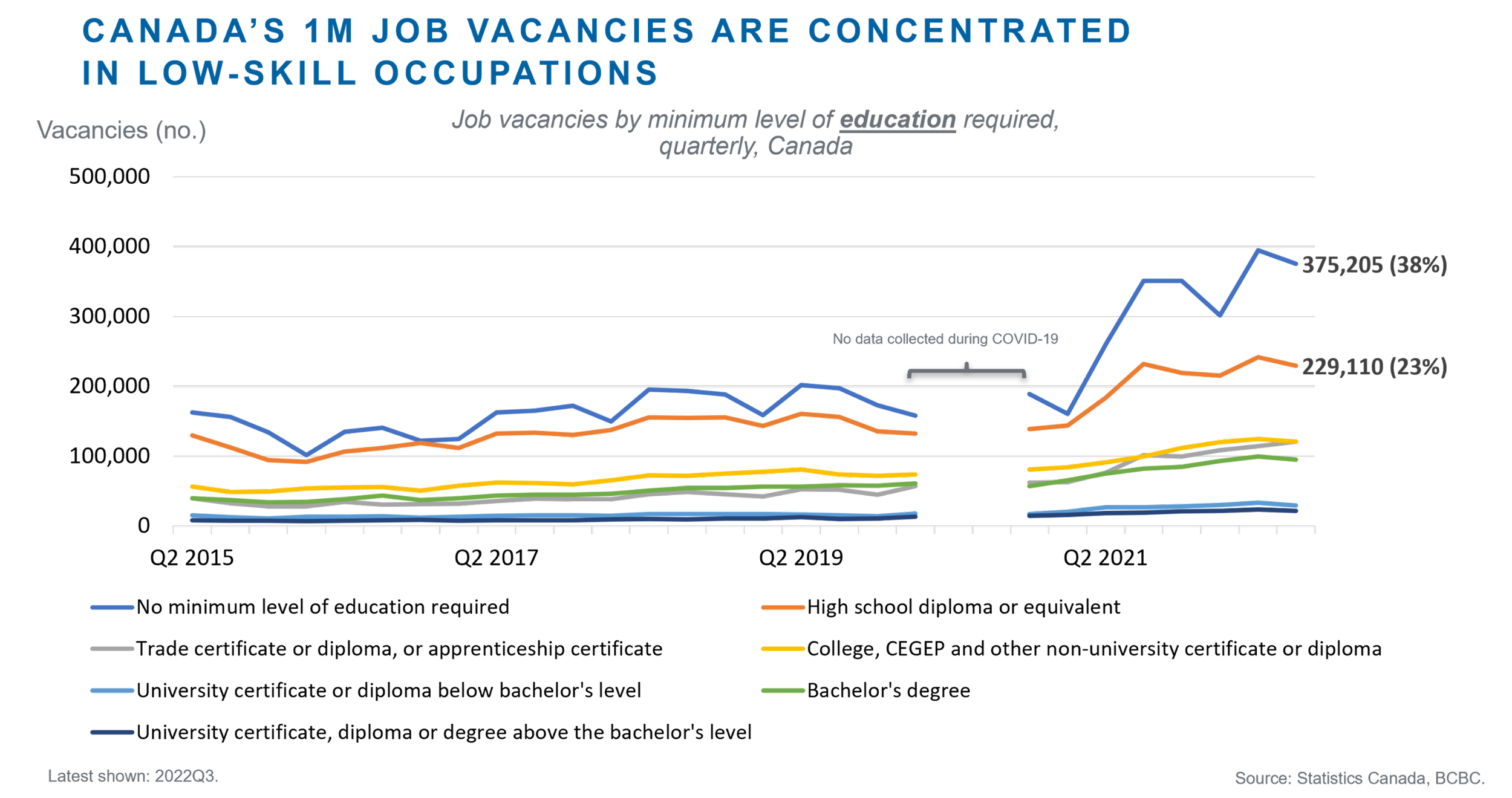

Canada has around 1 million job vacancies as at 2022 Q3. The vast majority are in entry-level positions requiring little or no experience or qualifications and paying low wages.Figure 1a shows vacant positions by level of education required. Around 375,000 vacant positions (38% of all vacancies) require no minimum education level. A further 229,000 (23%) require only a high school diploma. Over the past two years, unfilled positions requiring a trade certificate, apprenticeship or college certificate have increased modestly, but the number of vacancies requiring a bachelor’s university degree or higher has been flat.

With respect to the latter, Canadian firms have long expressed concerns about their ability to attract and retain “top talent” (high skilled labour). Talent attraction is a perennial challenge in Canada given our high tax rates and costs of living, and location next to the United States where salary opportunities are greater and tax rates and living costs are lower. Nonetheless, the data indicates that most of Canada's current 1 million job vacancies are in the low and mid-skill categories.

Figure 1a

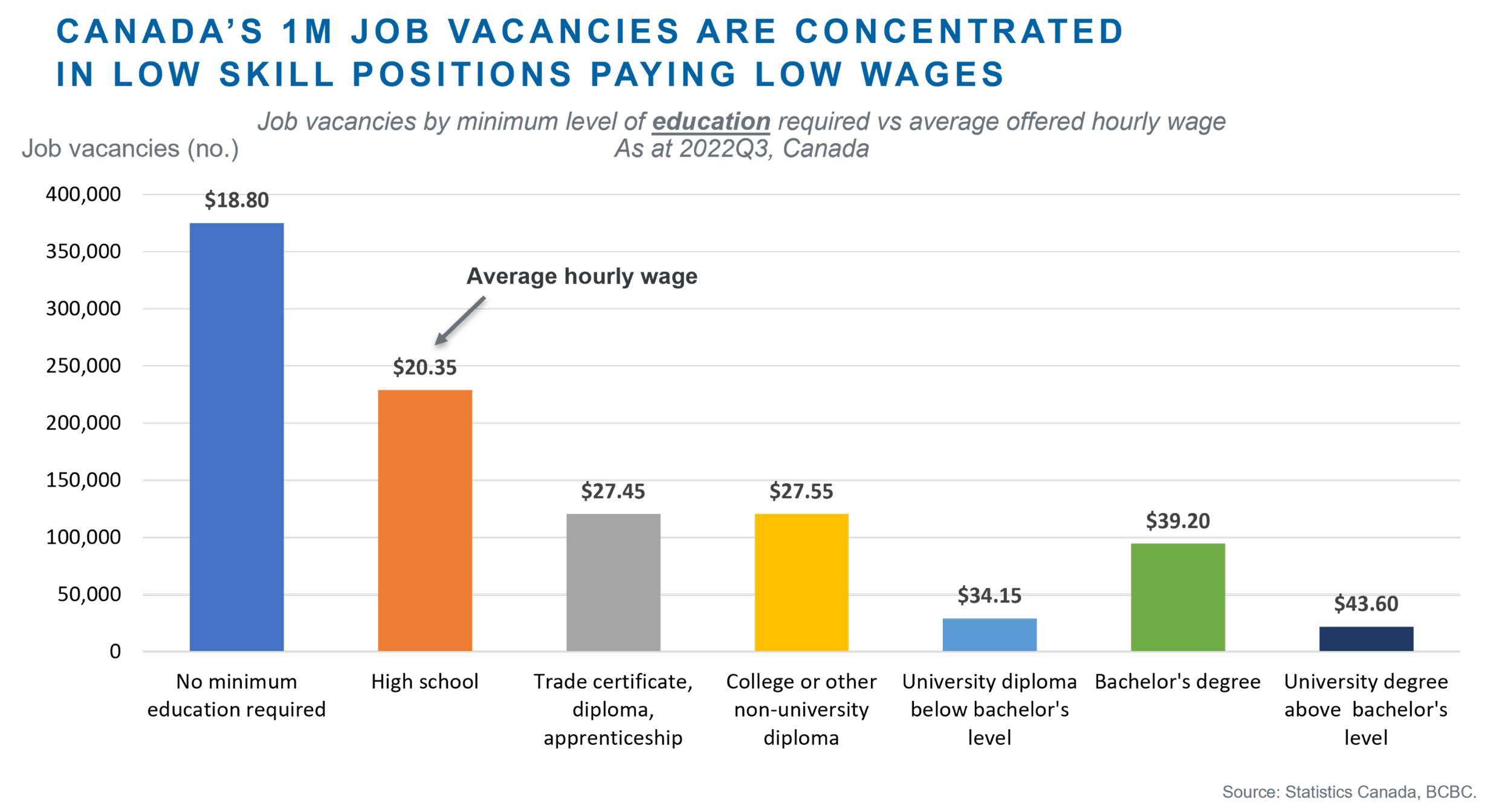

Figure 1b shows that the positions requiring no minimum education offer an average hourly wage of $18.80 while the average offered hourly wage for jobs requiring a high school diploma is $20.35. These are the lowest average wages among vacancies sorted by level of education required.

Figure 1b

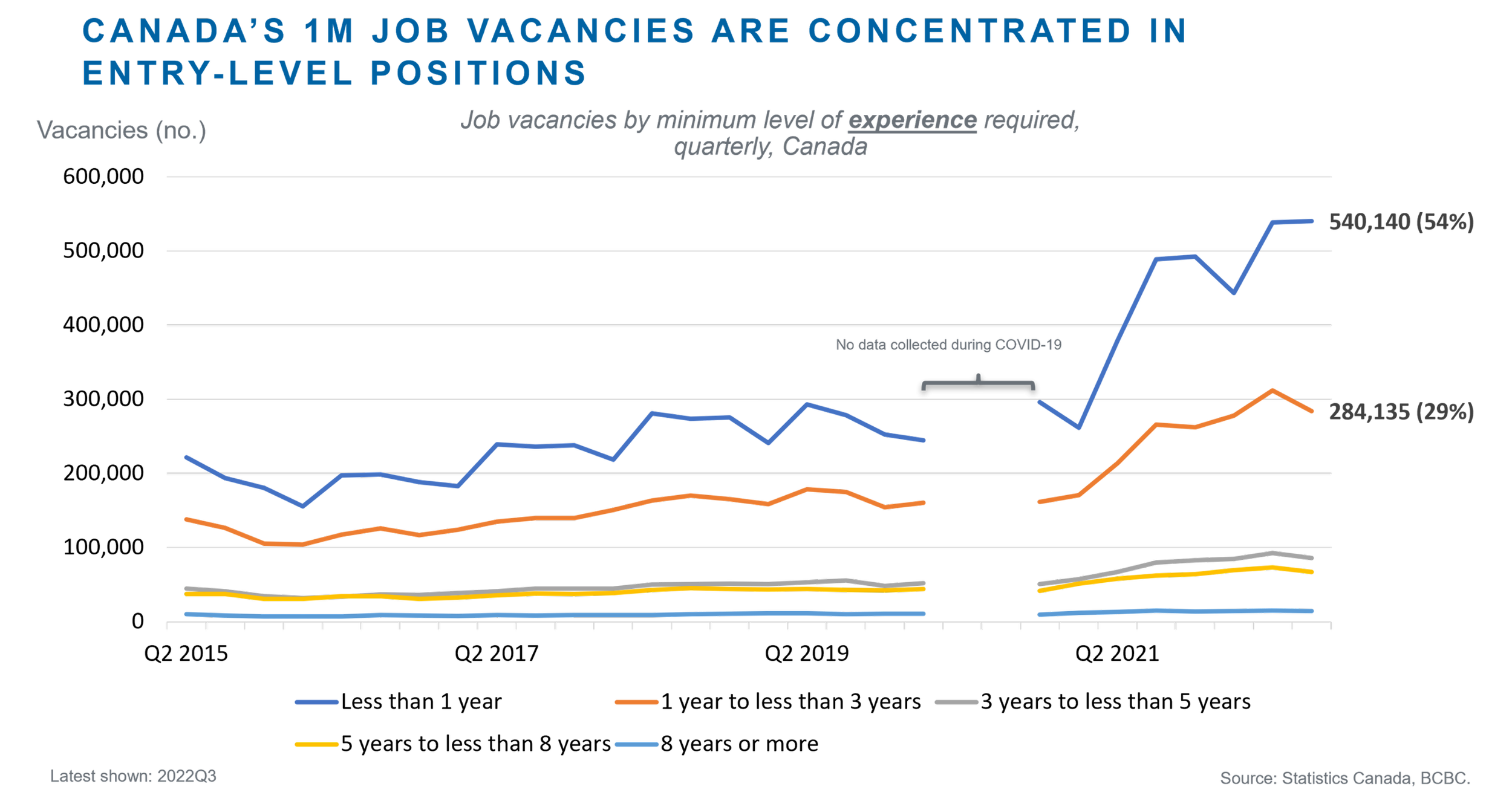

The overwhelming majority of current job vacancies also require little or no experience.

Figure 2a shows that around 540,000 jobs (54% of all vacancies) require less than a year of experience, while another 284,000 jobs (29%) require 1-3 years of experience.

Figure 2a

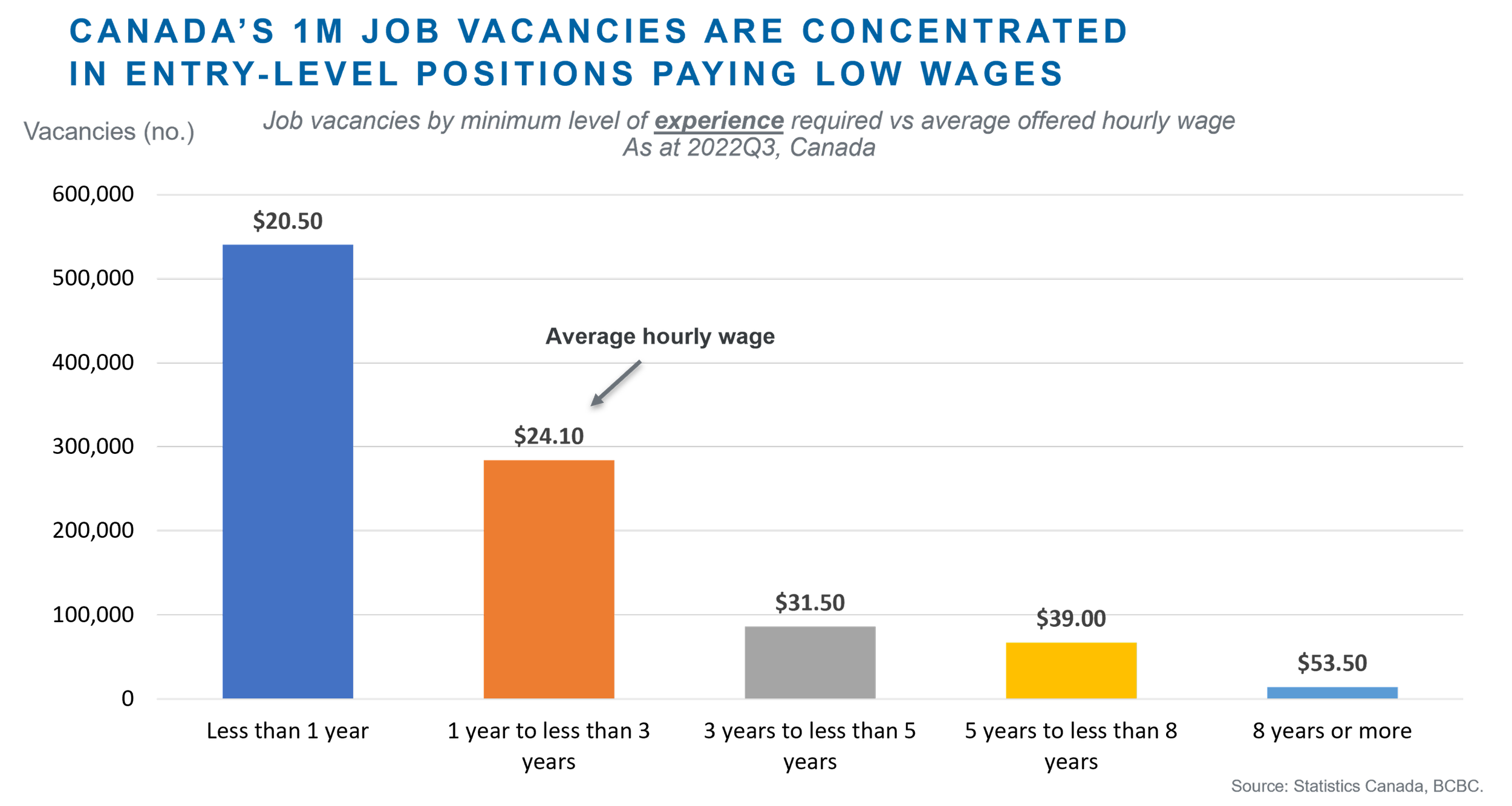

Figure 2b shows that the average offered hourly wage for jobs with less than one year’s experience is $20.50, rising to $24.10 for positions requiring 1-3 years’ experience. These are the lowest average wages among vacancies sorted by level of experience required.

Figure 2b

Job vacancies by occupation

Canada’s national occupation code (NOC) lists 500 specific occupations at the four-digit level. Table 1lists the top 20 job vacancies by occupation, representing 45% of all current vacancies. The top five are:

food counter attendants (74,000 positions, 7% of all vacancies);

retail salespersons (48,000, 5%);

cooks (28,000, 3%);

registered nurses (28,000, 3%); and

truck drivers (27,000, 3%).

Only 2/20 occupations require a university degree (shown in green), while 6/20 occupations require college education, specialised training or an apprenticeship (shown in orange). The remaining 12/20 occupations variously require some secondary school educcation, up to two years of occupation-specific training, short on-the-job training, or have no formal requirements.

Table 1

Conclusion

Immigration, not capital investment or productivity growth, remains at the centre of the federal government’s thinking about how to expand the Canadian economy’s productive capacity (Williams, 2023). The government has recently doubled down on this doctrine, citing “labour shortages” to justify its plan to raise temporary and permanent immigration to new record levels.However, the job vacancies data reviewed in this post reveal that most current vacancies are in entry-level positions requiring little or no qualifications or experience, and paying low wages. Why does the federal government lack confidence in the price mechanism to resolve structural imbalances in the labour market over time? Is it afraid of competition in labour (factor) markets? This question echoes the point made by University of British Columbia Professor David Green, one of Canada’s top labour market economists, in a recent Globe and Mail column. Finally, does it lack confidence in the ability of monetary and fiscal policymakers to cool overall demand in the economy and resolve cyclical imbalances in labour markets and product markets?BCBC has repeatedly expressed our concerns about the structural challenges facing the Canadian economy:

business investment that is barely keeping up with depreciation, resulting in a flat or declining capital stock per worker;

a two-decade retreat from international trade with exports shrinking as a share of GDP;

the highest private sector debt-servicing burden among G7 countries.

Young Canadians entering the workforce today already face the unhappy prospect of striving to earn a living in a jurisdiction with the lowest projected growth in average real incomes among the 38 OECD countries over both 2020-30 and 2030-60 (Williams, 2021; Williams and Finlayson, 2022). If the federal government intends to expand the labour supply explicitly to fill current job vacancies that are overwhelmingly in low-skill, low-experience positions paying low wages, it will be helping to keep Canada on that dismal path.Regrettably, Ottawa appears to have lost touch with, and interest in, lifting labour productivity, business investment per worker, exports as a share of GDP, real wage growth, and thus living standards for the average Canadian.