Failure to get stuff built – the role of regulation

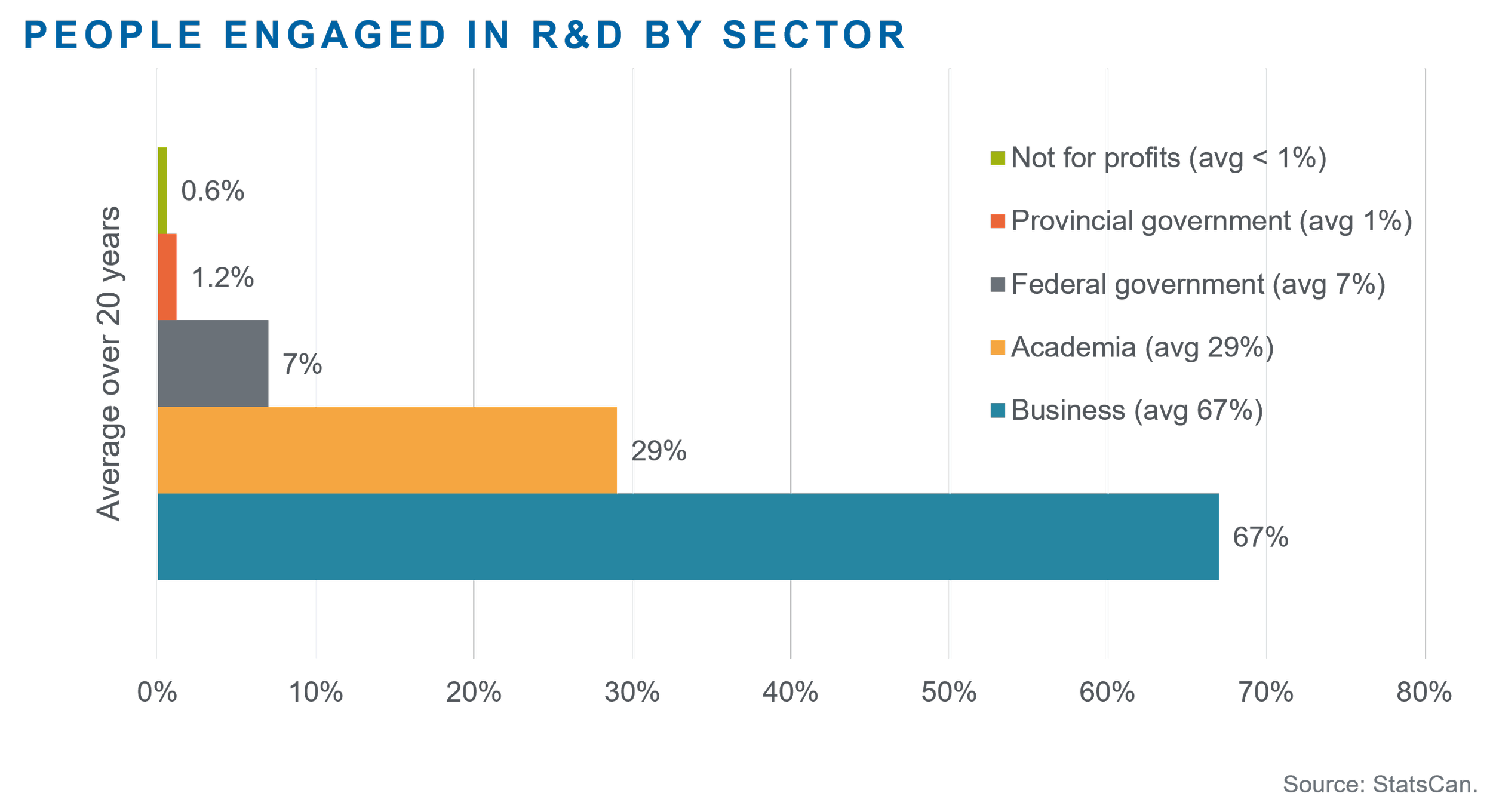

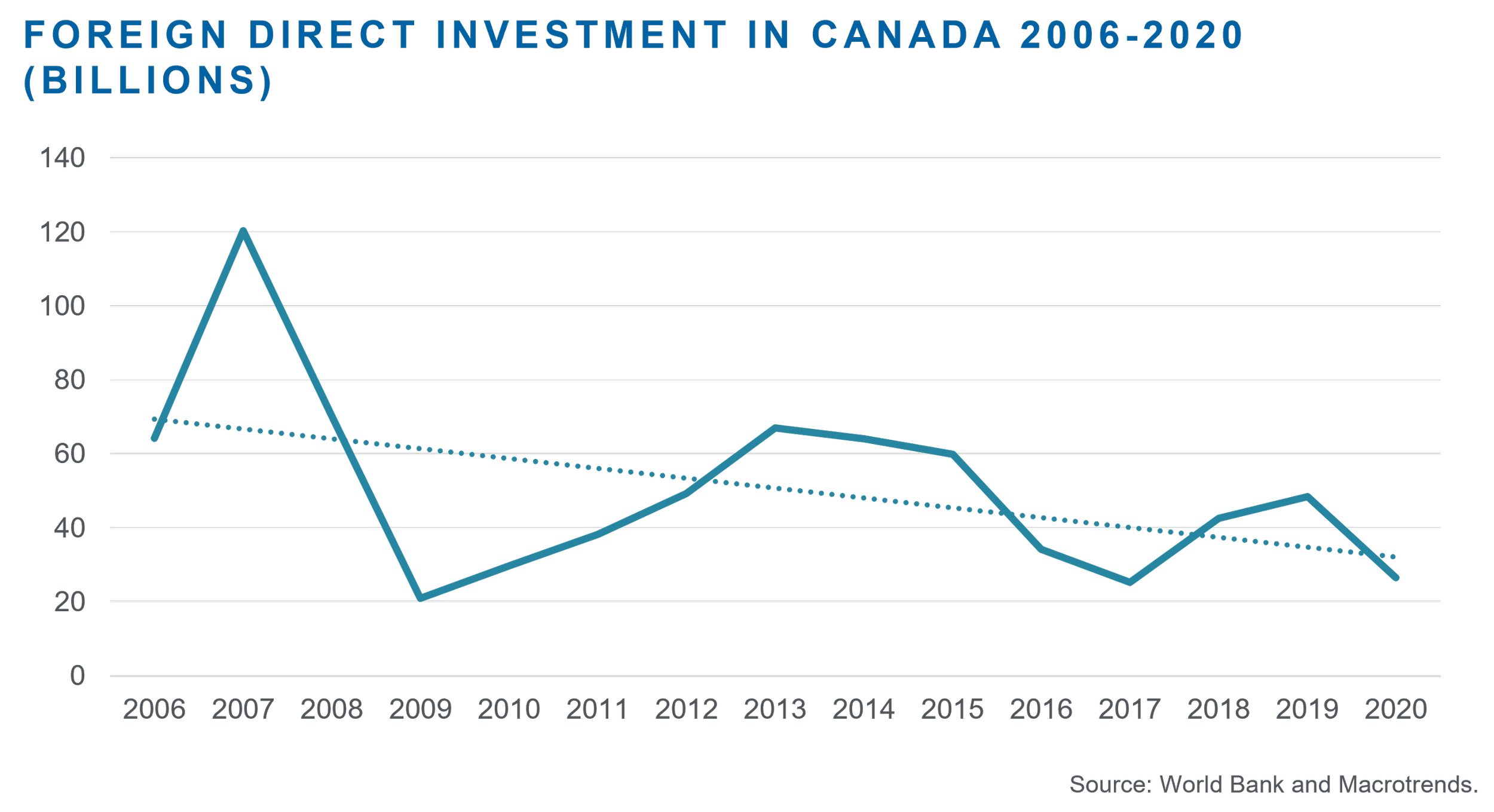

It’s the beginning of yet another year, and there are at least two key things we should worry about — our collective prosperity and its importance for citizen well-being. From a policy perspective, without the former, the latter is unattainable. Continued inflation for consumers and the cumulative impact of tax and fee increases on everything from greenhouse gases to employment and retirement funds over the past years are taking a hammer to Canadians’ standard of living. So, in the words of my colleagues, we must work smarter — not harder. [1] It is not a leap to understand that getting things built in our most economically productive sectors — including high-quality infrastructure that facilitates the movement of goods and enables trade and commerce — is critical to advancing our collective prosperity. As a small open trading economy, Canada and B.C. are places where exports lead to a general increase in economic activity [2] and well-paying jobs by leveraging our existing comparative advantages. [3] The prized outcomes of innovation, new technology, and solutions to various challenges — including, for example, environmental ones — come in significant part from basic “first dollar” income generated by our trade-exposed sectors. This is true in part because business has the greatest number of people involved in innovation (Figure 1), a consistent number over the past 20 years despite flagging foreign investment [4] (Figure 2) and an increasing tendency of Canadians (and their pension funds) to invest outside of the country. But the bottom line is we are falling behind economically [5] and can only course-correct with some bold moves to get things built. Reforming today’s complex, costly, duplicative, and time-consuming regulatory processes is a good place to start. In an increasingly challenging and uncertain geopolitical context, it’s imperative.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Canadians from coast to coast generally appreciate the rule of law and understand the need for sensible rules and regulations. While some rules are important, regulators often make the mistake of adding another rule or more processes believing this will increase certainty, clarity, and investment prospects. In fact, Canada’s approach to regulation and regulatory decision-making is producing the opposite outcome. We operate with bloated regulatory processes that bring higher costs and more complex and time-consuming administrative procedures with every new government intention paper, regulatory amendment, and policy announcement. When it comes to the cumulative regulatory burden on businesses and citizens, it’s hard to keep track. So, when investors hear it may take up to 10 years or more to slow-walk through project approval requirements with no certainty of a positive outcome until a press release is issued, who can blame many for turning their backs on Canada and B.C.?

Often government officials try to “sell” our regulatory processes to investors by promising speedy reviews. This is a myth. Guidance documents on project approval processes published by the federal and B.C. governments suggest an enticing 1.5 years [6] for governments to do their duty. Of course, companies must develop the supporting material to facilitate project reviews — so add several years to the tally, resulting in a minimum best-case period for review of perhaps four years. And this does not include the time-consuming, cumbersome, and often conflicting adjunct permitting and licensing processes for infrastructure and significant industrial projects. One need only go through the available project databases to see that the estimate of up to a decade is not an imaginary number.

What profit-seeking private sector investor would choose to participate in what is fast becoming a regulatory “vetocracy,” where anyone (even people not resident in Canada) can raise an issue or concern, creating a chain reaction of hand-wringing and decision-making paralysis leading to endless delay? This is a major issue for all levels of government, who often talk about the importance of a vibrant economy, yet increasingly are unable to advance real, on-the-ground economic development — whether in housing, roads, ports, energy infrastructure, or natural resources. What can be done to make us more attractive for investment, at least from a regulatory perspective? Several things come to mind.

First, fully embody the “whether to” principle underlying the purpose of environmental/project assessment processes. It should not take a minimum of four years to determine if a proposal is in the national, provincial, or local interest. It shouldn’t even take 1.5 years to make such a decision. In fact, meeting our collective goals related to both prosperity and greenhouse gas emissions means we should aim for approval processes no longer than two years in total (including permitting), an idea that is now gaining traction in the energy-starved European Union.

Second, moving beyond ceaseless deliberation to making decisions, even in the face of some inevitable opposition, especially for strategically important projects and activities, is essential, not least to burnish Canada’s increasingly tattered reputation as a place for greenfield projects. Dithering hinders economic activity, slows business development, repels investment, and ensures we miss critical opportunities. For Canada, LNG is a standout case in point. Critical minerals could be next, notwithstanding the federal government’s apparent enthusiasm to make Canada a critical minerals superpower. Undoubtedly, expanding the country’s electricity system – necessary to get even part-way to meeting the political dream of “net zero” — will be another painful example of how difficult it has become to get stuff built in Canada.

Third, there can be no project development in our most productive and revenue-generating export sectors without Indigenous partnerships in both decision-making and investment. This does not mean offloading responsibilities to project proponents but instead calls for creating mechanisms to enable Indigenous participation in the ownership of projects. Governments have obligations to assist Indigenous people with building governance, administrative, and technical capacity. Moving more quickly is essential.

Fourth, to help expedite decision-making, developing a joint Indigenous-provincial-federal list of projects considered significant and endorsed by all relevant governing bodies (Indigenous, provincial, and federal) would send positive market signals. The Business Council also suggests substituting provincial for the federal environmental assessment process, as is currently sometimes done in B.C., should be the default approach to project reviews across the country. This respects the provincial lead role in development while acknowledging the shared environmental responsibilities.

Finally, Canada and B.C must reorient our narrow, inward-looking approach to managing GHG emissions to one that is more holistic and global in outlook and orientation. In B.C.’s case, our less GHG-intensive export goods —the ones demanded by the world — contribute positively to tackling the collective problem of global emissions. Getting projects built and moving our lower GHG-intensive products to market should be a priority, even if this adds to domestic emissions.Prosperity occurs when an open economy harnesses the talents of citizens, protects property rights so investment can flow, adopts smart regulation with timely decision-making, embraces competition, encourages innovation, and ensures the availability of high-quality trade-supporting infrastructure. The inability to get stuff built is a failure of political leadership and represents a missed opportunity for Canada. We can and must do better.

[1]https://bcbc.com/insights-and-opinions/how-does-b-c-s-labour-productivity-growth-compare-with-other-provinces-and-countries

[2] https://bcbc.com/insights-and-opinions/a-brief-primer-on-b-c-s-export-base.

[3]https://bcbc.com/insights-and-opinions/which-industries-pay-the-bills-for-british-columbia-an-update , https://bcbc.com/insights-and-opinions/which-industries-pay-canadas-bills.

[4]https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?end=2021&locations=CA&name_desc=false&start=1970&view=chart.

[5] https://bcbc.com/insights-and-opinions/how-does-b-c-s-labour-productivity-growth-compare-with-other-provinces-and-countries

[6]https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/environmental-assessments/guidance-documents/2018-act/time_limits_and_extensions_policy_may2021.pdf (page 5) ; https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/services/policy-guidance/the-impact-assessment-process-timelines-and-outputs.html.