OECD predicts Canada will be the worst performing advanced economy over the next decade…and the three decades after that

Ottawa’s economic growth strategy rests on four shaky pillars: accommodative monetary policy to support interest-sensitive sectors of the economy like credit, housing investment, and durable goods consumption; expansive fiscal policy guided by short-term "guardrails" and lacking a long-term fiscal anchor; record immigration levels to turbocharge population growth and housing demand in major cities; and a national childcare policy to marginally raise GDP through slightly higher labour force participation (page 54 of the federal budget concedes the policy, if fully implemented, will yield only five hundredths of a percentage point (0.05 pp) of additional real GDP growth per annum over the next 20 years).

The political class appears to have lost interest in efforts to raise workers’ productivity and real wage growth through higher business investment per worker, faster innovation adoption, and getting the average company to operate at scale.

Was Canada able to grow real incomes over 2007-2020?

A recent OECD report shows the extent to which Canada’s efforts to stimulate demand for interest-sensitive sectors of the economy and boost labour supply growth helped to raise real per capita GDP growth over 2007-2020. As discussed in our previous blog, the short answer is: Ottawa’s policies did not help a whole lot.

Canada’s real GDP per capita grew by 0.8% per annum over 2007-2020, ranking us in the third quartile among advanced countries. In other words, we were towards the back of the pack but not at the very bottom. That’s about to change – and not for the better. Other countries are predicted to move ahead of us in making their economies more productive while Canada’s economy stagnates.

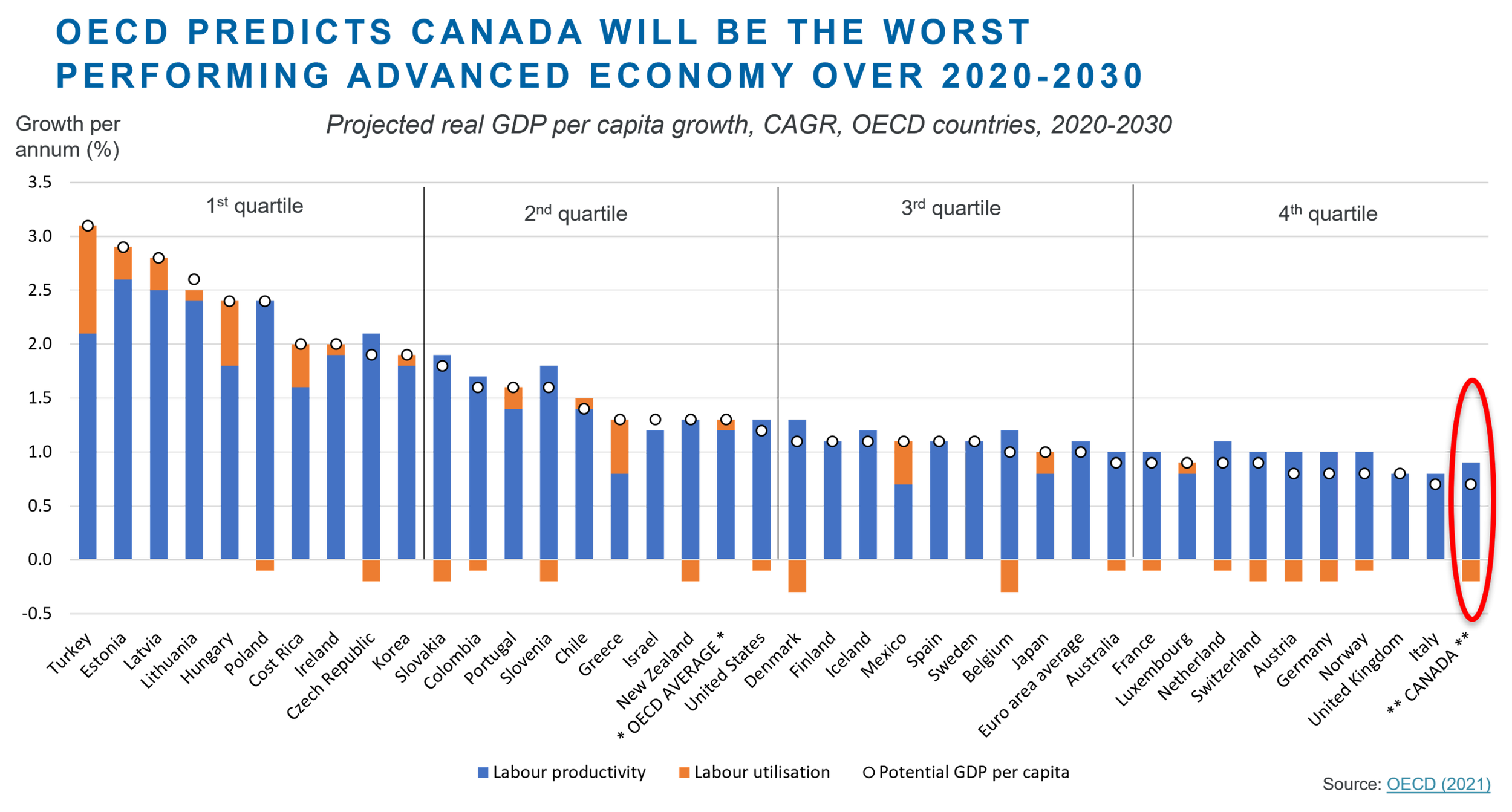

Canada will be the worst performing advanced economy over 2020-2030

The same OECD report offers insights on whether Canadians can look forward to meaningful gains in average living standards in the decades to come. The findings are sobering. The OECD predicts Canada can at best achieve real per capita GDP growth of only 0.7 percent per annum over 2020-2030 (Figure 1a).This places us dead last among advanced countries.

Figure 1a

What’s driving this? A previous blog explained how growth in real per capita GDP is the sum of: (a) growth in output per hour worked (“labour productivity”) and (b) growth in hours worked per head of population (“labour utilisation”). Of the two components, productivity growth is the more important determinant of future living standards because it is limited only by the pace of technological change and the ability of businesses and workers to adapt to it. In contrast, labour utilisation growth has a natural ceiling based on demographics, labour force participation, and there being only so many hours people can or will work per year.

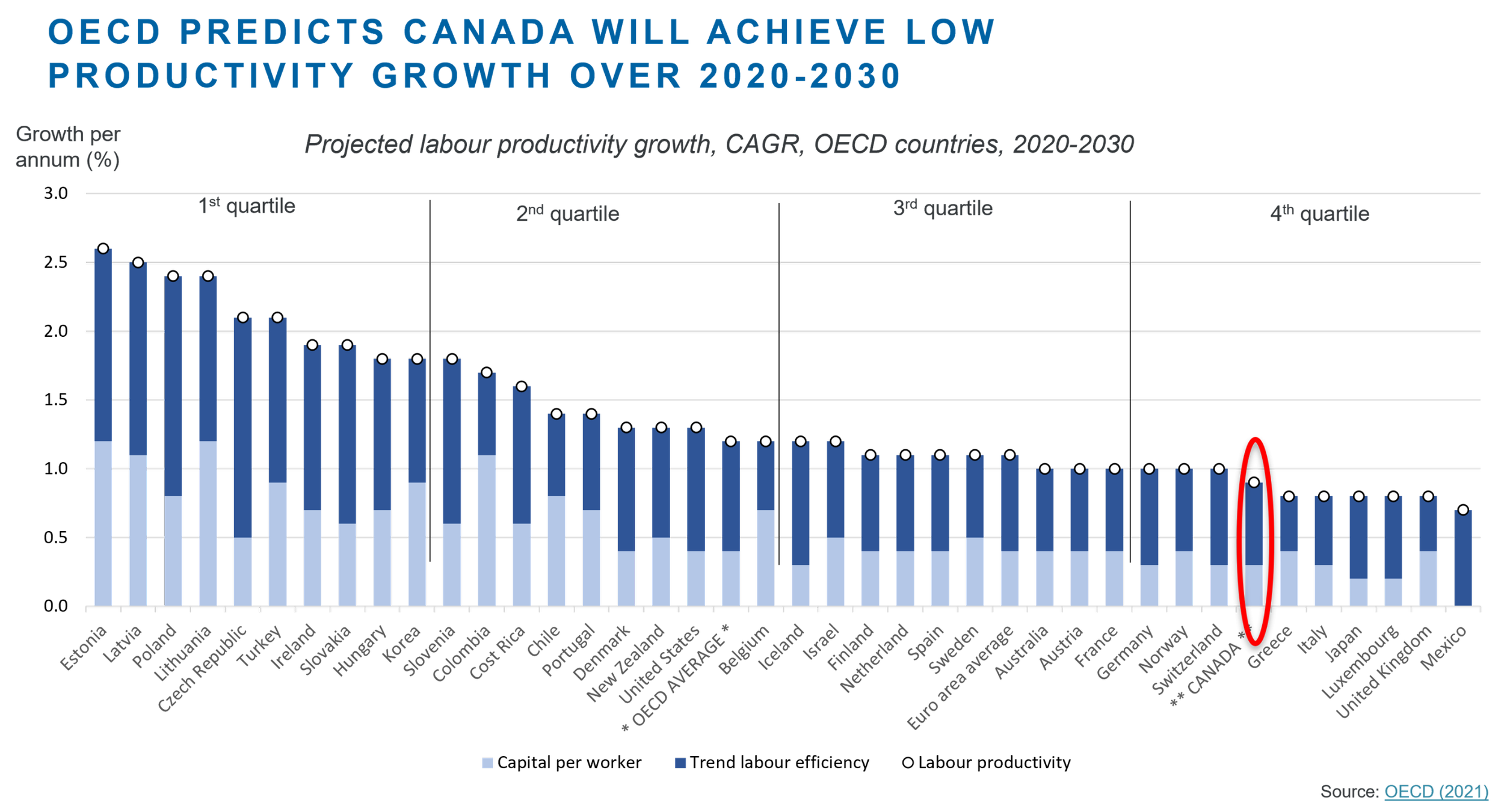

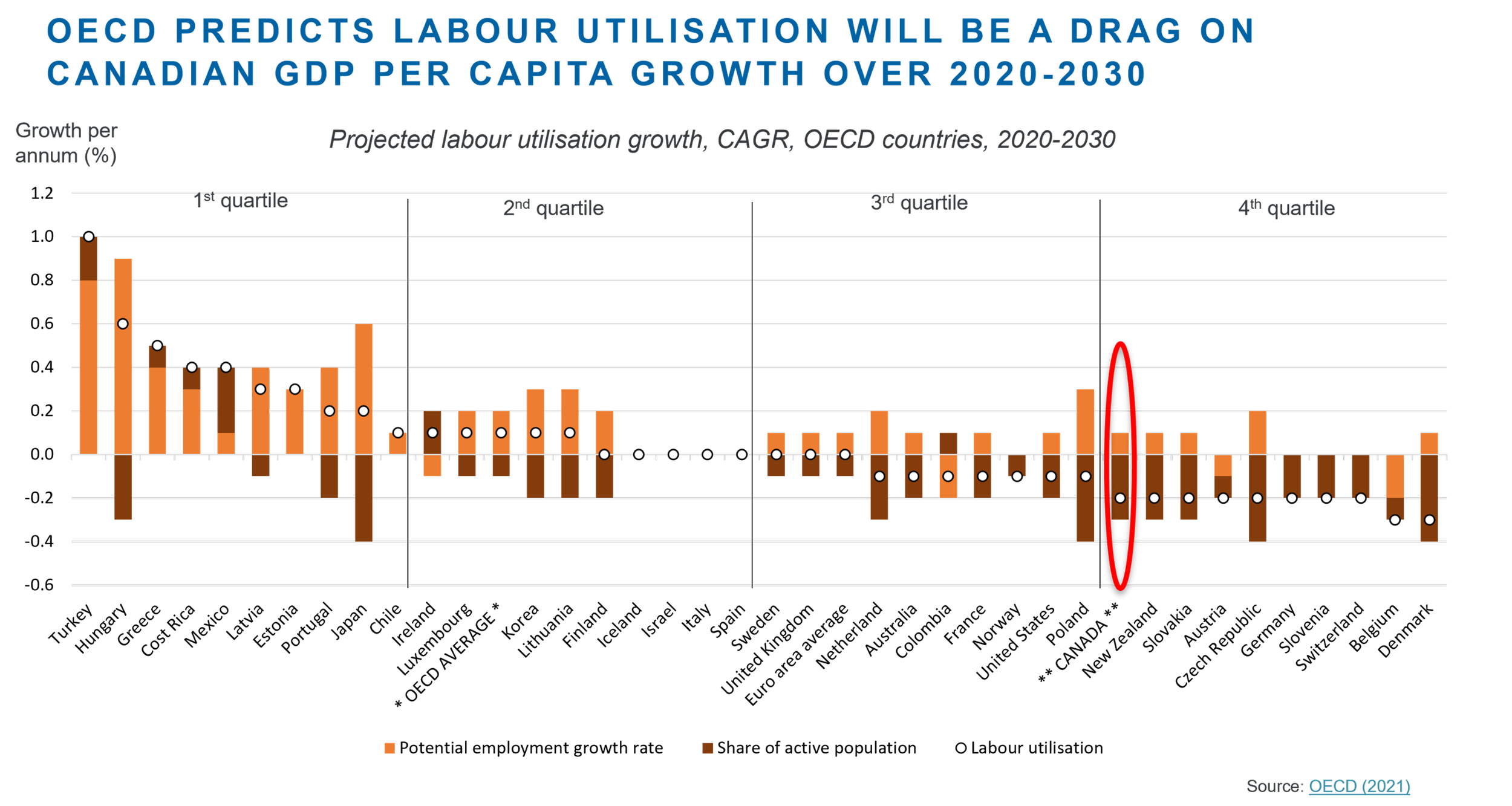

T he OECD finds that Canada’s prospects for real per capita GDP growth over 2020-2030 are poor because of feeble expected growth in output per hour worked (labour productivity, see Figure 1b) and a slight drag from hours worked per head of population (labour utilization, see Figure 1c).

Figure 1b

Figure 1c

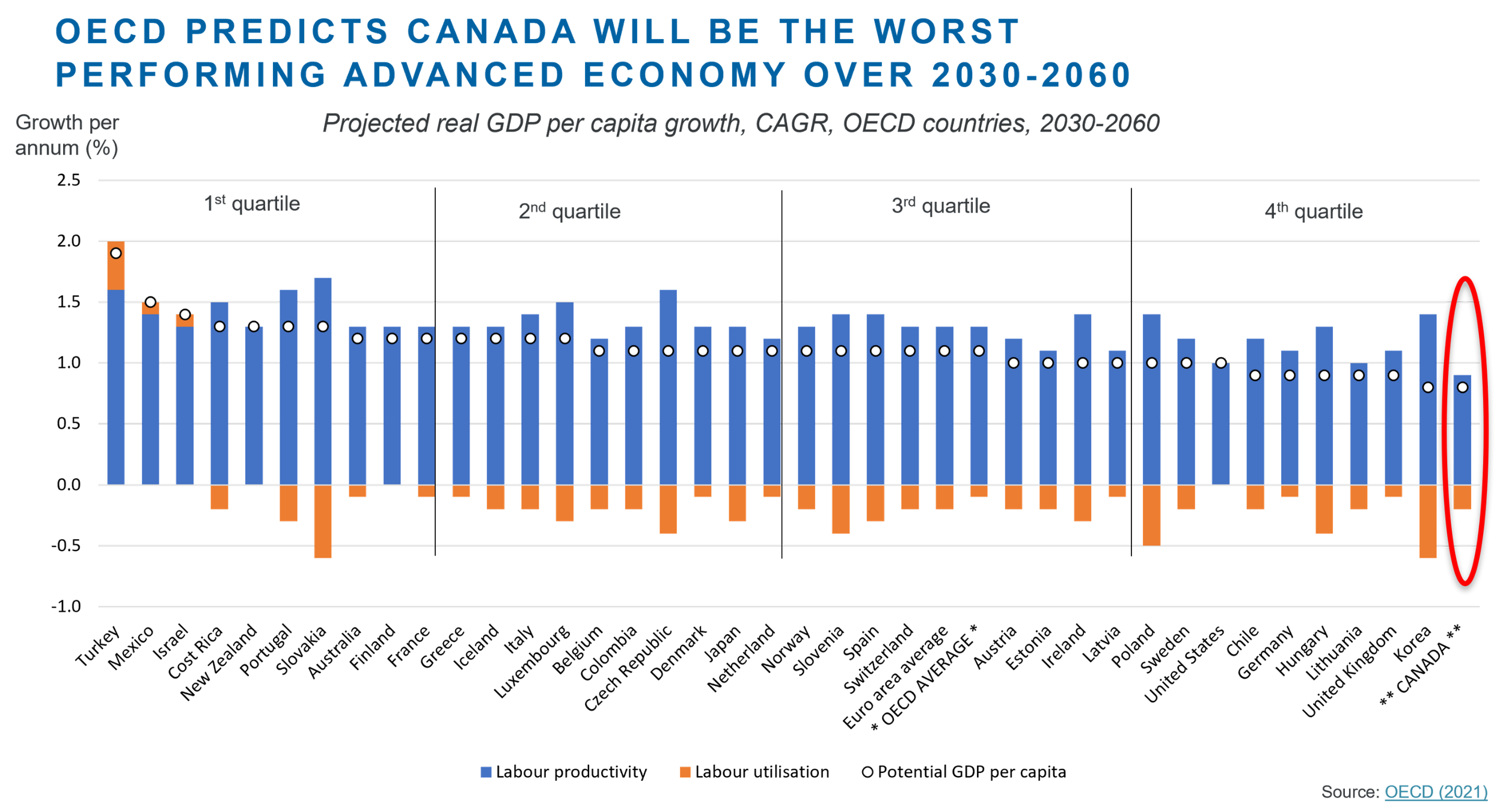

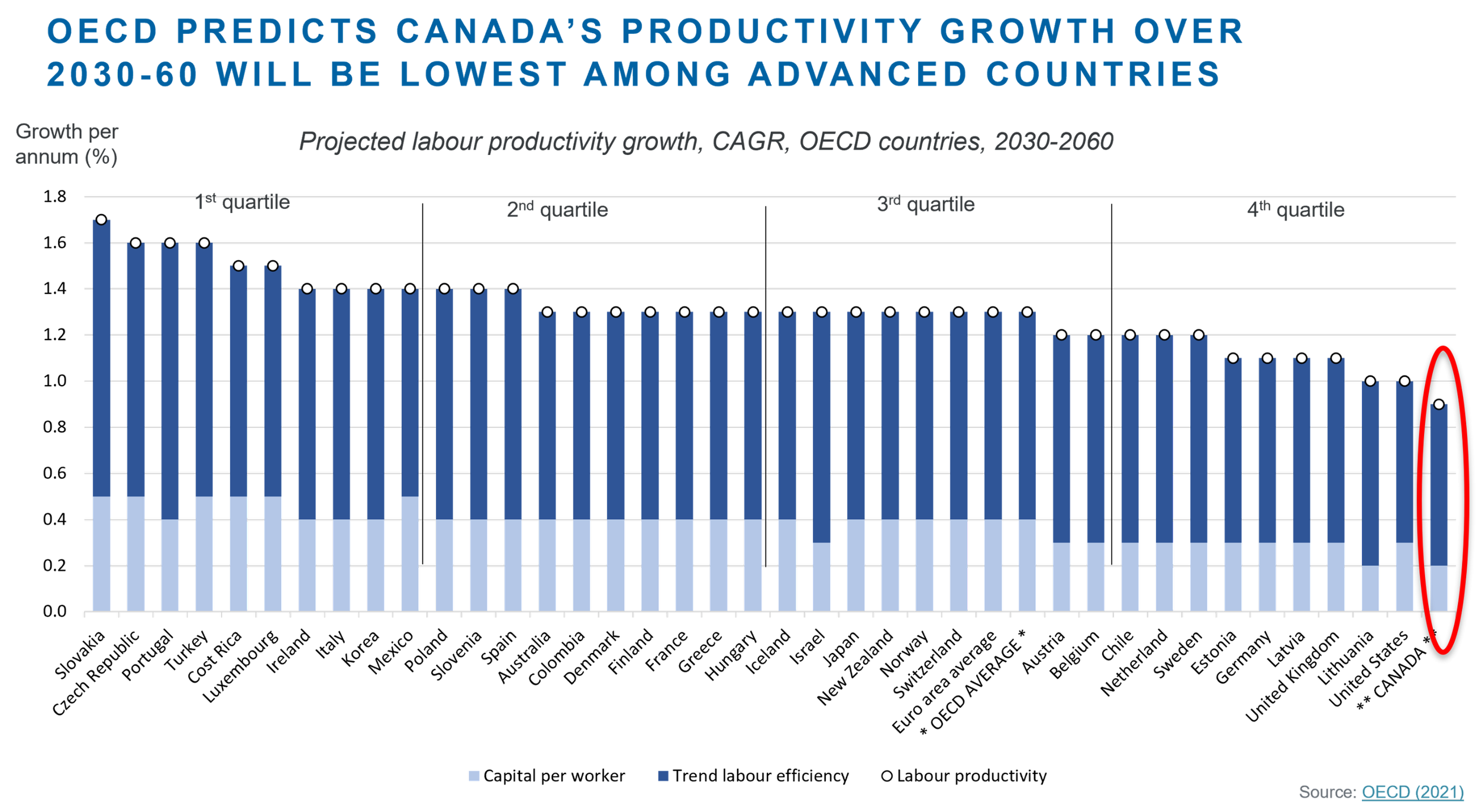

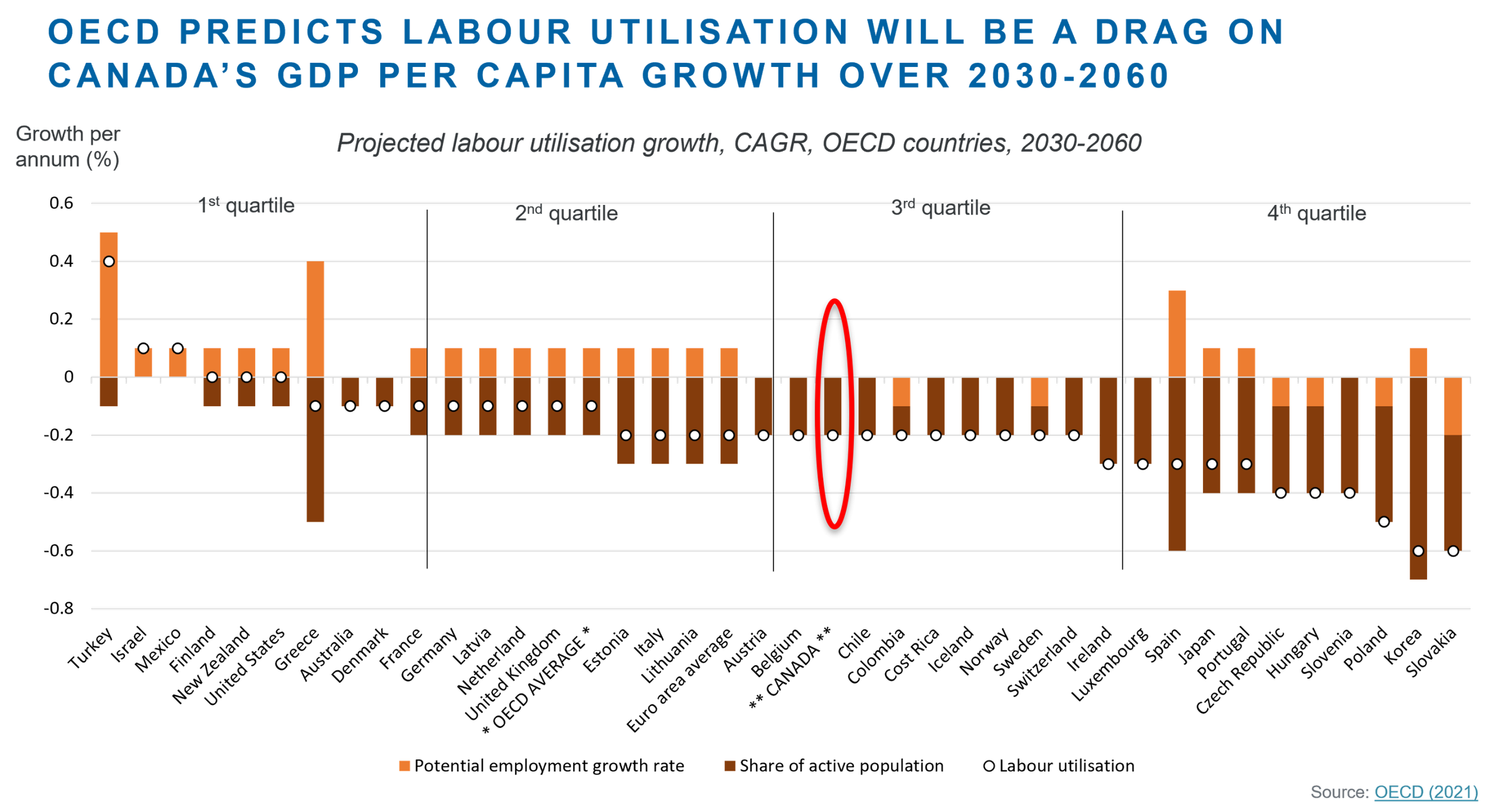

Canada will also be the worst performing advanced economy over 2030-2060

Unfortunately, the next decade is not an aberration. The same OECD report projects Canada will also post the worst economic performance among advanced countries over 2030-2060, with real per capita GDP advancing by just 0.8 percent per annum (Figure 2a). In other words, Canada will be dead last not only for the next decade, but also for the three decades after that.

Figure 2a

What’s driving this? Once again, the OECD finds that Canada’s prospects for real per capita GDP growth over 2030-2060 are poor because of low expected growth in output per hour worked (labour productivity, see Figure 2b) and a modest drag from hours worked per head of population (labour utilisation, see Figure 2c). Most notably, as Figure 2b shows, Canada’s productivity growth is expected to the lowest among advanced countries over 2030-2060.

Figure 2b

Figure 2c

Conclusion

Past generations of young Canadians entering the workforce could look forward to favourable tailwinds lifting real incomes over their working lives. That’s no longer the case. If the OECD’s long-range projections prove correct, young people entering the workforce today will not feel much of a tailwind at all. Rather, they face a long period of stagnating average real incomes that will last most of their working lives. On average, Canadian living standards and our quality of life relative to other countries are set to decline as other countries make their economies more productive.

Long range projections are not certain. But in providing a glimpse of a possible future, they offer us an opportunity to reflect and make a course correction lest they become reality.

It is time for Canada’s political class to rethink their priorities and take steps to create the conditions for a more productive economy. This will require some hard thinking and expertise about how to raise labour productivity growth and real wage growth through higher business investment per worker, faster innovation adoption, and adjusting the incentives (and disincentives) facing Canadian companies aspiring to operate at scale.